MAY 22, 2024: Yesterday we went to visit Dunnottar Castle and barely saw it in the haze. This morning, we woke up in a campground not too far away. Visibility was better and I wanted to return to the castle. It was on my must-see list was I not yet ready to give up on it.

We drove early to the castle parking, and while Mark said his morning prayers, I followed the path back to the coastline. It was spectacular! The tagline for the official Dunnottar Castle website is Once Seen, Never Forgotten. I couldn’t agree more.

The castle sits on a 160-foot-high rock, surrounded on three sides by the sea. It was once the home of a powerful family. Mary Queen of Scots, visited in 1562, and during the civil war in 1645, the castle was plundered. In 1717, after being the seat of Clan Keith for over 400 years, the castle was sold. At that time, anything valuable – like floors, ceilings, and furniture – was removed, leaving just the stone walls. In 1919, Lord and Lady Cowdray bought the ruins and began restoring and protecting the castle from further damage. It reopened after the work was completed and is still owned by the same family. Today, the castle is open to the public.

Now, in the early morning, the castle had not yet opened to go inside, but at least I got to see it from the outside. Upon returning to the motorhome, we then drove north to Aberdeen.

In Aberdeen, we had an appointment with Itai, a young Israeli living there, to see the synagogue . The synagogue is located in the city center, and we were very lucky to find a large parking spot immediately in front of the building.

Itai had invited another couple to meet us there – Jennie and Brian. Jennie and Brain are from Fraserburgh, an hour north of Aberdeen. Why Itai had invited them all this way to join us, soon become apparent.

Aberdeen Hebrew Congregation was founded in 1893, serving a small number of Jewish residents – mainly immigrants from Eastern Europe. The modest, current synagogue, located on Dee Street, was opened in 1945 and is the northernmost active synagogue in the UK. There is no rabbi at Aberdeen and services are led by members of the community once a month. This year there was a Purim event with nine children, which was considered a big success. During our visit there, we got to see their Torah scrolls which come from the Memorial Scrolls Trust, an organization dedicated to preserving and distributing Torah scrolls that survived the Holocaust. Mark was even able to help Itai put a new torah cover on one of the scrolls.

Above the main sanctuary, on the second floor is a community room where we sat with Itai, Jennie and Brian. They told us about their congregation and we were very grateful to have met them. Especially interesting was Jennie’s story.

Jennie grew up with the knowledge that her mother, Elizabeth, was born in London in 1943, and had been left in a war time babies home when she was two weeks old. Jennie’s grandmother promised to collect her baby after the war, but that never happened. The woman who ran the home raised Elizabeth as her own child.

Elizabeth confided later in life that during her lifetime she ‘felt she didn’t belong anywhere’. She had no roots. Ten years ago, in 2014, shortly before she passed away, Jennie encouraged her mom to write down every detail she could remember about her background. Jennie wanted to find her family for her and to give her mother a sense of belonging and rootedness. Sadly however, her mother died before Jennie discovered anything.

A few months later, with the help of leading genealogists and historians, her grandmother’s records were located and Jennie discovered that her mother, and therefore she herself, was Jewish. Her grandfather had been a highly decorated Polish Officer under British command (meaning he belonged to a Polish military unit that was formed in the UK after Poland was occupied by Nazi Germany). Her grandmother came from a wealthy Jewish family and her maiden name had been Rothenberg. At the time of Elizabeth’s birth, the grandmother had also been serving in the army. Since uncovering her Jewish identity, Jennie and her husband have become active in the Aberdeen Jewish community.

Jennie is a photographer by profession and her work includes photographs that capture the Jewish experience in Aberdeen. Some of her other projects include working with communities that have experienced profound loss and trauma, focusing on their resilience – the strength that rises from hardship. Through powerful portraits, she documents Holocaust survivors and victims of terror in Israel. You can learn more about Jennie’s important work by visiting her website.

After the synagogue visit (exactly one hour, before our parking time limit ran out) we drove to the Grove cemetery in Aberdeen. A formal Jewish burial ground was established there in 1910. Grove cemetery was not too large, and we eventually found the Jewish section. It is not enclosed by a wall or fence, but is set apart in its own distinct area.

After the cemetery, we then drove an hour north to Fraserburgh, the location of the Museum of Scottish Lighthouses. The museum has a display about lighthouses and also offers guided tours to visit the Kinnaird Head Lighthouse, the first lighthouse in mainland Scotland.

We had a few minutes to look around the museum before the tour started.

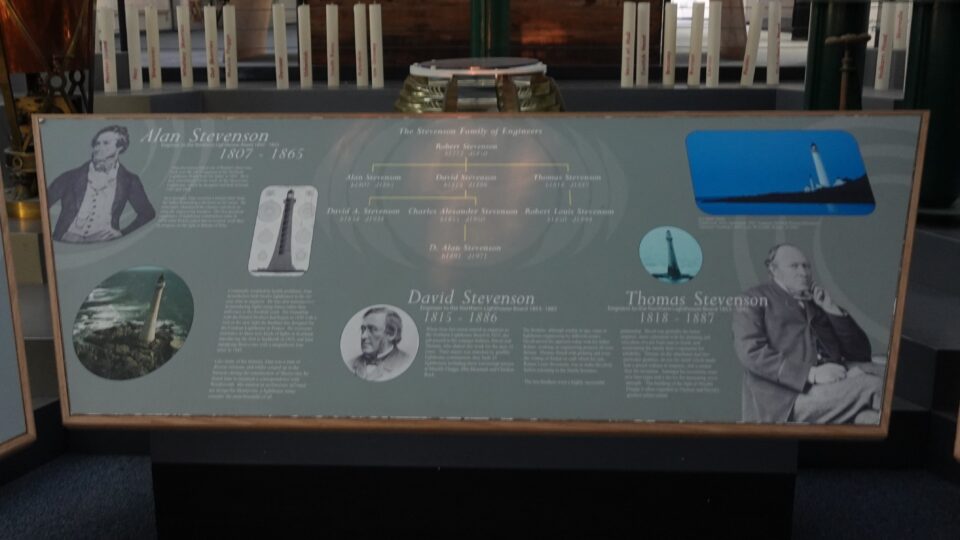

Part of the museum was devoted to the history of lighthouses in Scotland and the important role of the Stevenson family. Over four generations, from the late 18th to the early 20th centuries, members of the Stevenson family designed and built some of the most important and enduring lighthouses along the Scottish coastline. It began with Robert Stevenson (1772–1850), and continued with his sons—Alan, David, and Thomas—and later his grandsons. Together, they created a network of over 90 lighthouses, blending groundbreaking engineering with elegant design, and dramatically improving maritime safety. Their legacy left a lasting impact on lighthouse engineering worldwide.

Just as the tour began, the rain started pouring. We walked to the Kinnaird Head Lighthouse getting wet. This lighthouse is special, not only because it was mainland Scotland’s first lighthouse, but also because the building was first a castle. Instead of tearing down the castle, they built the lighthouse inside it.

We learned that each lighthouse flashes its light at unique intervals, following a specific on-and-off pattern that serves as its identifying signal. This signal allows ships to recognize and navigate by them. This particular lighthouse flashes once every 15 seconds.

Kinnaird Head Lighthouse started operating in 1787 and worked until 1991 (over 200 years!). Instead of converting it to an automated system, it was preserved as a historical monument. A small automated lighthouse was built in front of this one. The automated lighthouse is run remotely from Edinburgh by the Northern Lighthouse Board.

We entered the original lighthouse in the castle and climbed the circular staircase up one flight. This room used to be the dining room of the castle, but once the building was converted to a lighthouse, it was used to store a year’s supply of paraffin for the lighthouse lamps, until the lamps were switched to electric.

We climbed up one more flight, and entered the chamber of the trainee. Since this was the oldest lighthouse in operation, trainees came here to learn how to operate a lighthouse and then be sent elsewhere. The system worked using a Dead Man’s Shoes system. The only way to be promoted was when someone died or retired.

Some of the lighthouses are on rocks in the middle of the ocean, and the lighthouses keepers, usually a team of four to man the lighthouse 24/7, would need to get supplies shipped in.

The main task the lightkeepers had was to ensure the light was always on from dusk to dawn. After climbing one more flight, we reached the heart of the lighthouse – where the actual light is. The light here was just a simple bulb that was surrounded by a set of slotted lens that turn around the single bulb.

The lenses magnify the light so that it can be seen miles away. The rotation of the lenses determines the rate of flashing. The lenses rotates around the bulb using a set of gears that are in the middle of the staircase. These would rotate the mirror for 20-minutes, after which the lighthouse keeper would need to wind the gear mechanism, similar to winding a grandfather clock to keep it going.

From the room with the light bulb, we went onto a small balcony outside at the top of the lighthouse. From here we could see the new, small, automated lighthouse and the foghorn. Lighthouse keepers used to also need to man the foghorn – a very loud horn that would sound when visibility was low. Today foghorns are no longer in use because technology on ships lets them operate in fog without the help of a foghorn.

To summarize what we learned, each lighthouse has a flashing light that goes on and off according to a pattern that identifies the lighthouse. The pattern is caused by rotating lenses around a light in the center. The rotation is done using a set of gears and weights that hang in the middle of the lighthouse tower. I found learning all this quite fascinating.

From the museum, it was a short drive to our campground for the night. The weather was stormy but inside the motorhome, all was dry, warm and cozy. It had been a very interesting day.

0 comments on “Aberdeen and Our First Lighthouse”Add yours →