Of all the relatives I’ve known, my grandfather Sabi stands out as the most illustrious – he was accomplished, respected, and perhaps even revered. He also happens to be the person who unintentionally had the greatest influence on my life and the lives of my children.

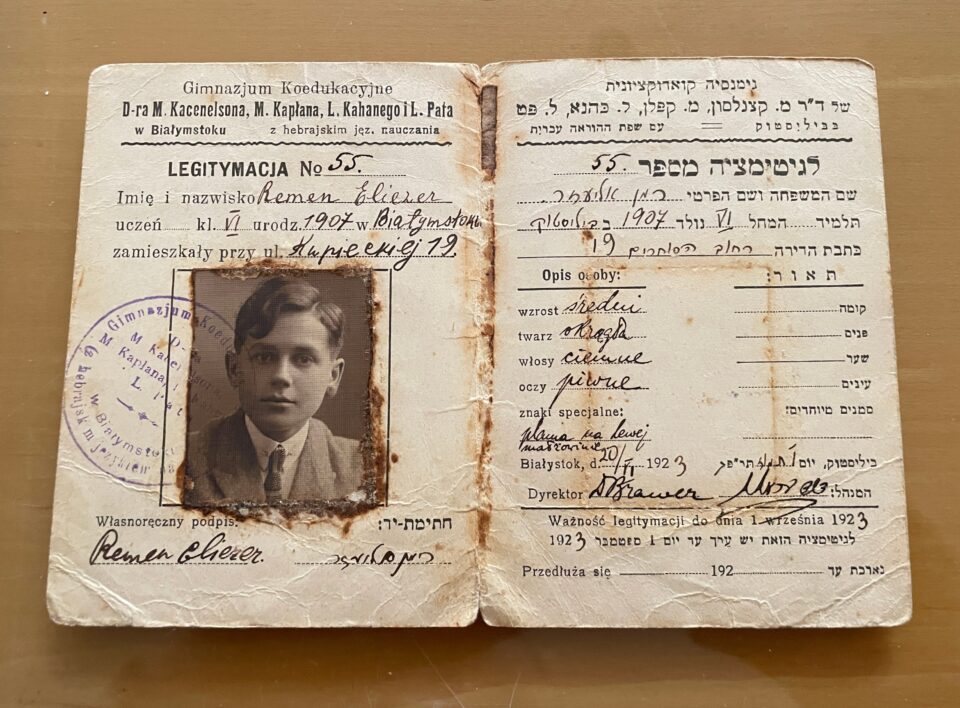

Lazar Remen—known as Sabi—was born in 1907 in Bialystok, Poland to Leib Aryeh and Nechama Remen. My middle name, Nechama, is in honor of his mother. He was one of four siblings: Hershel, his older brother, and two younger sisters, Leche and Dobche.

When Sabi was born, Bialystok was a bustling city of over 65,000 people, the majority of whom were Jewish. It was a vibrant center of Jewish religious, cultural, political, and economic life—renowned for its synagogues, yeshivas, Jewish schools, and a wide array of Zionist, socialist, and Bundist organizations.

Economically, it was a key textile and manufacturing hub, with many Jews owning workshops and small businesses. Sabi’s parents ran a shop that sold ribbons, ropes, and straps. In fact, the Polish word for straps is ramiączka, and my mother, Sabta Yona, believed that the family name “Remen” may have originated from that word.

As a teenager, Sabi attended the Hebrew Gymnasium, the first and only high school in Bialystok where all instruction was conducted in Hebrew and aligned with Zionist ideals.

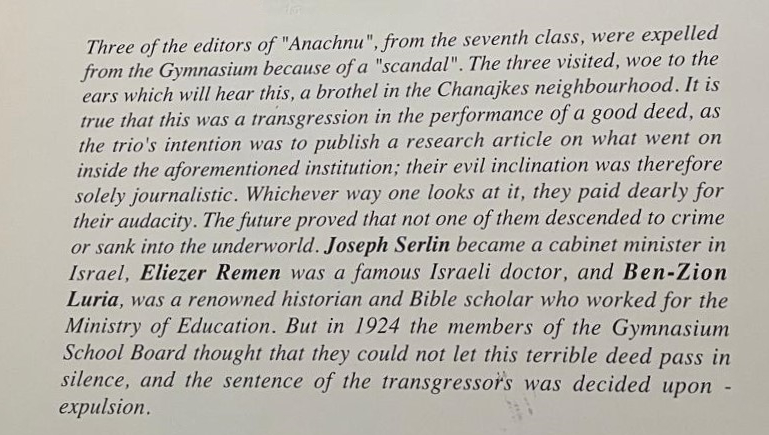

While in 11th grade, he wrote for the school newspaper and, in a bold move, he and two classmates visited the local Jewish brothel for an investigative story. This stunt led to all three being expelled—a tale he did not share with his children. Instead, my mother grew up believing he left school due to political activism. The true story only surfaced later, documented on page 44 of a book about the Hebrew Gymnasium.

After being expelled in 1924, and with a strong Zionist upbringing, Sabi was eager to move to Palestine. When he approached the relevant immigration organization, he was advised to first learn a profession before making aliyah. Following that advice, he enrolled in medical school in Cologne, Germany.

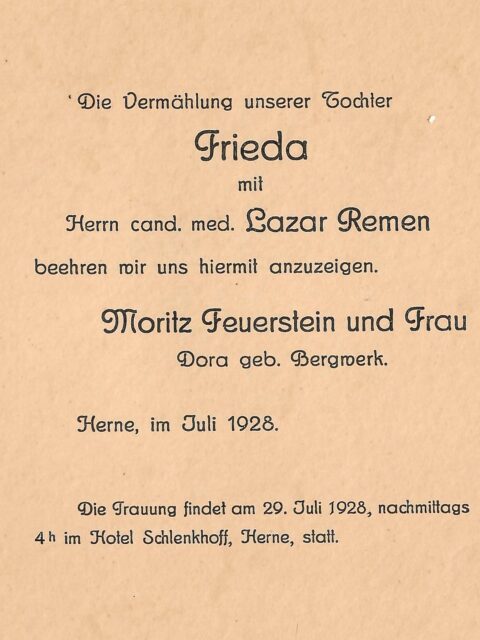

To earn some money during his studies, he gave Hebrew lessons. One of his students was a cousin of my grandmother, Frieda Feuerstein—known to us as Sabti—who introduced the two. They married in Herne in July 1928, when Sabi was just 21 and Sabti only 20.

Sabi had to promise Sabti’s father (my great-grandfather, Opa) that the newlyweds would remain in Germany. So, after completing his medical exams in 1930, Sabi opened a practice in Cologne, instead of moving to Palestine.

Despite being early in his career, he made a significant medical contribution. In 1932, he was the first to describe the use of an anticholinesterase drug—neostigmine—to treat myasthenia gravis (MG), a chronic autoimmune disease. His findings, which showed rapid and dramatic improvement in patients’ muscle strength, laid the groundwork for a treatment still used today. His work actually preceded Mary Broadfoot Walker’s paper, which is considered to be the landmark article on this, by two years.

In June 1931, his first child, my mother Yona Shifra was born.

Then, in 1933, Sabi awoke one morning to find the window of his medical office defaced with antisemitic graffiti. The exact content varies in family accounts—some recall “Juden Raus,” others mention a cross—but the message was clear enough. That incident convinced him it was time to leave Germany. With determination, he packed up his family and moved to Palestine.

Sabi’s brother-in-law, Nati, later told me that he believed Sabi’s foresight to leave came from his Eastern European background. Unlike German Jews who felt more assimilated, Sabi had grown up in Poland, where Jewish-Gentile relations were often more fraught. That experience, Nati thought, gave him the clarity to recognize the warning signs and act on them. Without his vision and courage, I—and many of his descendants—might not be here today.

0 comments on “Family Stories:

Grandfather Sabi – Part 1”Add yours →