MARCH 5, 2025: Yesterday, we explored Jewish heritage sites in central Milan. For today, we hired a private driver to take us to several sites outside the city center. Most, but not all, of what we would see today is Jewish cemeteries. Usually, I describe the sites we visit in the order we see them, from morning to evening, but for today’s visits, it makes more sense to present the cemeteries in historical order.

In 1597, when Milan was under Spanish rule, Jews were officially banned from the city and were only allowed to return in 1800 under Napoleon. No traces remain of any Jewish burial sites from before 1597. Since 1800, four locations in Milan have been associated with Jewish burials—and today, we visited all of them. Who would have thought that visiting cemeteries could be so interesting – but it actually was.

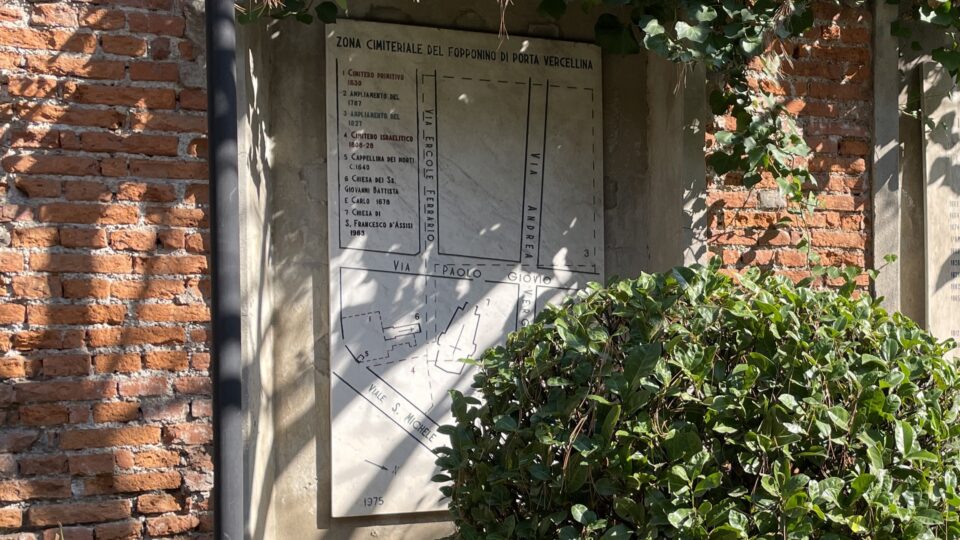

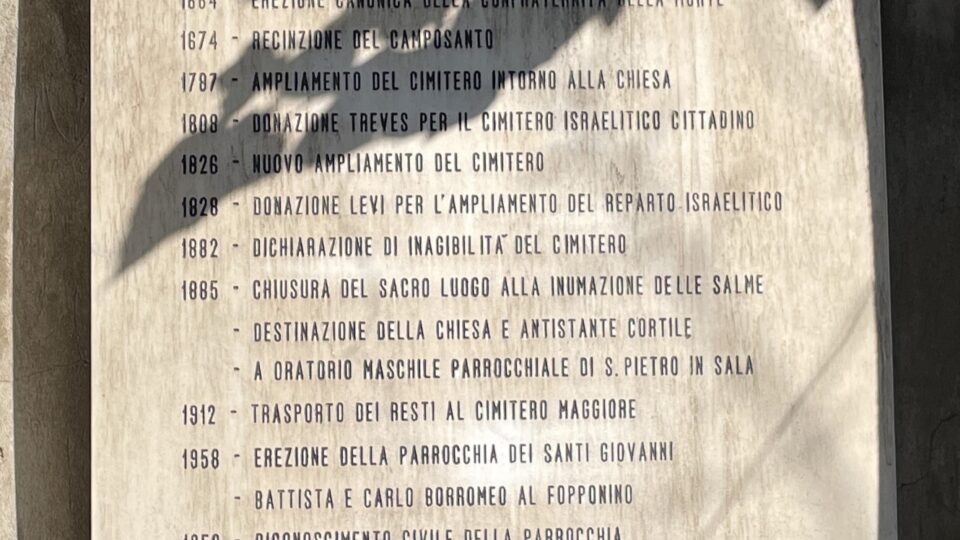

When Jews were permitted to return to Milan, an official burial ground was designated in 1808—the Ancient Jewish Cemetery at Fopponino. Though the cemetery no longer exists, two plaques commemorate its history: one displays a map of the former cemetery with the Jewish section marked, while the other outlines key events, including contributions from benefactors Treves and Levi. The cemetery was closed in 1895, and in 1919, the remains of those buried there were transferred to the Jewish section of the Monumental Cemetery.

The Monumental Cemetery of Milan (Cimitero Monumentale) is one of the city’s unique tourist destinations. More than just a burial site, it is an open-air museum, renowned for its elaborate tombs, artistic sculptures, and grand mausoleums. It serves as the final resting place for many notable figures, including prominent artists, writers, and politicians. Opened in 1866 near the city center, the cemetery’s Jewish section was inaugurated in 1872.

The Jewish section is positioned to the right of the main entrance and has its own separate gate. Upon arriving we found this entrance was closed. Peering through the locked gate, we could see several ornate tombstones and, directly ahead, a funeral hall with stained glass windows. It was disappointing not to be able to explore further.

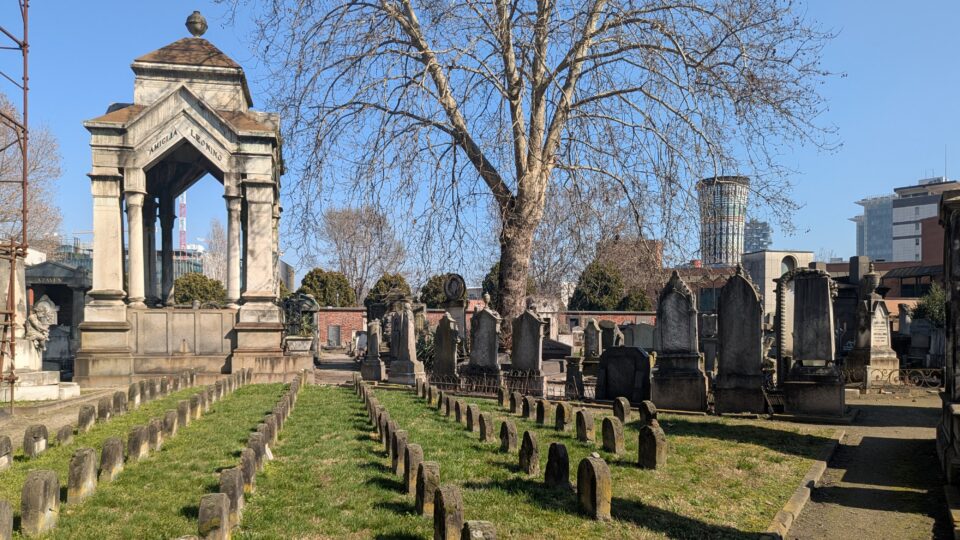

Instead, we entered Monumental Cemetery through the main gate and eventually found an alternative way into the Jewish section. Over the years, we have visited many Jewish cemeteries, but this one stood out as unlike any other. The Jewish community here appeared to have adopted the architectural customs of the prevailing Christian culture, resulting in grand, elaborate monuments like those found in the non-Jewish section.

The Jewish section also contained ossuaries (structures for storing bones after decomposition) and columbaria (chambers for housing cremated remains) – burial practices that are not typical in the Jewish tradition.

The funeral hall building we spotted from the locked gate was restored in 2014. It has six stained glass panes each one depicting two of the Twelve Tribes of Israel. It was designed by Diego Penacchio Ardemagni, who drew inspiration from Marc Chagall’s windows at Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem.

Also in the Jewish section was a memorial stone plaque set around a large marble menorah. This was erected in 1946 to commemorate the local Jewish victims of the Holocaust who were never given a burial.

Among all the ornate tombs, we saw two grassy areas with rows of old graves. Here, many inscriptions had faded beyond recognition, and where text remained, it often displayed only the name of the deceased, with no dates. I suspect that these may be the relocated remains of those originally buried in the Ancient Jewish Cemetery at Fopponino, but I have not found any evidence to confirm this.

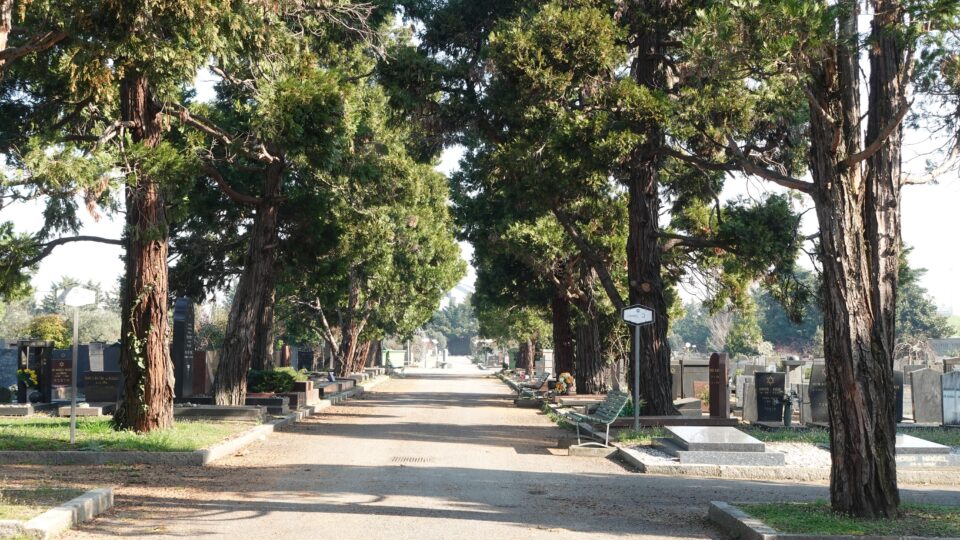

Cimitero Maggiore di Milano, located on the outskirts of Milan, was opened in 1895 to address the city’s growing need for burial space, as the Monumental Cemetery was reaching capacity due to Milan’s expanding population. From that point on, the Jewish section of Monumental Cemetery only accepted burials of illustrious Jews, a practice that continues to this day.

Today Cimitero Maggiore di Milano is the largest cemetery in Milan, spanning 678,624 square meters – roughly the size of 95 football fields – and contains over 500,000 graves. Within this huge complex, are two Jewish sections – Plot 8, within the walls of the cemetery, and the Cimitero Ebraico (Jewish Cemetery), right outside of the main cemetery walls.

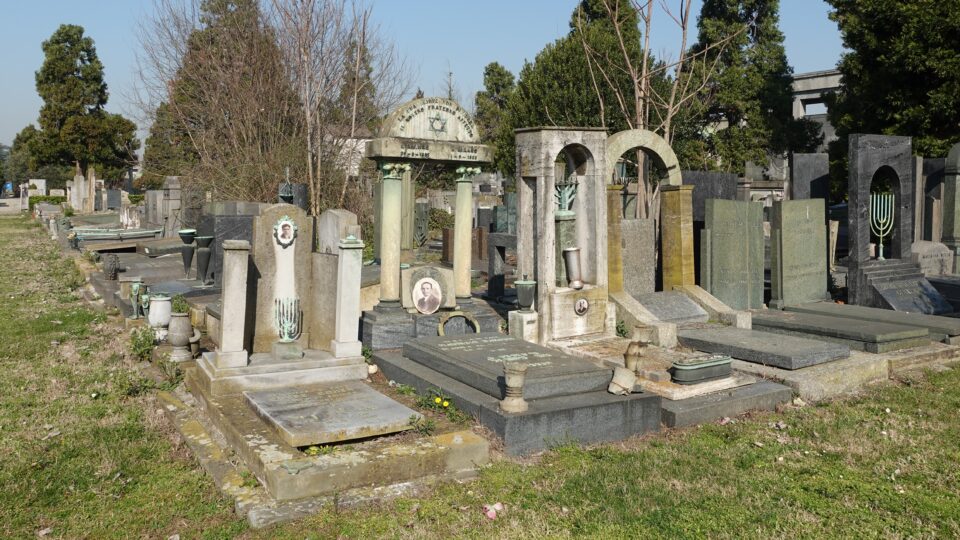

When Cimitero Maggiore opened in 1895, the Jewish Community (then known as the Israelite Consortium) applied for and was granted Plot 8 in the new cemetery. This section was in use from 1895 to 2010. I found it unusual that many of the tombstones in this area featured photographs of the deceased, a practice probably influenced by a similar custom in the non-Jewish sections of the cemetery.

The second Jewish section in Cimitero Maggiore, Cimitero Ebraico, was established in 1936 and remains in use today. The gravestones here are simpler and adhere to traditional Jewish customs, often adorned with menorahs and Jewish stars in various shapes and sizes.

During our visit, a funeral procession was taking place. The deceased was being transported in a wooden coffin in the back of a slow-moving hearse, with the associate rabbi of Milan walking alongside and chanting the traditional funeral prayers. A small group of mourners followed.

In addition to visiting these cemeteries, today we also went to GARIWO – The Garden of the Righteous of the World. Inaugurated on January 24, 2003, this is a memorial space dedicated to the women and men who have helped the victims of genocide, persecution and totalitarian regimes all over the world. The garden is located in the large Monte Stella Park, on a hill formed by the accumulation of rubble caused by Allied bombing. Modelled on Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, each “Righteous One” is remembered with a memorial stone or plaque.

In 2019, the Garden of the Righteous was renovated and a pathway was created. This pathway leads you along the memorial stones and plaques, where you can read the names of the Righteous and a short description of what they did.

In Milan, the first memorials were dedicated to Moshe Bejski for the Righteous of the Shoah, Pietro Kuciukian in honour of the Righteous of the Armenians, and Svetlana Broz for the Righteous against ethnic cleansing in the Balkans.

As we walked along the path, there were several names we recognized such as Aristides de Sousa Mendes (the Portuguese consul who helped the Jews to leave France) and Primo Levi (the writer who bore witness to the Holocaust). On the GARIWO website, there is a list of all those honored in Milan which includes Khaled Abdul Wahab (a Tunisian Arab who saved Jewish lives during the Holocaust), Marek Edelman (vice commander of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising), Dimitar Peshev (rescued 48,000 Bulgarian Jews from deportation) and many others related to helping Jews.

Currently in the garden there are 87 names. This year, in Milan, the new righteous names for the garden will be revealed in a ceremony on March 11, just a few days from now. I am curious to see who they will recognize.

Another stop on our itinerary today was the Centro di Documentazione Ebraica Contemporanea (CDEC), or the Center for Contemporary Jewish Documentation. Established in 1955, it is an independent institution dedicated to promoting the study, culture, and history of the Jewish people in Italy, focusing on modern times. Although it was the middle of a workday, the building was locked shut when we arrived.

Only in doing research for writing this blog, did we learn that in June 2022, the center moved to the Shoah Memorial, that we had visited yesterday. The library we saw at the memorial is now part of the new CDEC headquarters. Besides the library, the new headquarters houses departments of Education, Historical Research, the Anti-Semitism Observatory and an Archive.

Once we finished visiting all the places on our list, instead of returning to our apartment, we went with our Jewish Orthodox driver to the Bande Nere neighborhood, the area of the city where she and most of the other observant Jews live. Bande Nere is primarily a residential area with mid-20th-century apartment buildings, parks, and green spaces that give it a nice atmosphere.

As we drove through the neighborhood, our driver pointed out the Jewish landmarks—synagogues, schools, old-age home, kosher grocery stores, and restaurants. The area reminded me of the Upper West Side of Manhattan, known for its strong Jewish presence, but with one key difference: in Milan, everything seemed discreet, almost hidden. She would point to a nondescript building and say, “This is a synagogue,” yet there were no visible signs distinguishing it from the surrounding structures. Even the Jewish school blended in seamlessly with the residential buildings. Here, everything operates under the radar—without someone directing you to the right place, it would be nearly impossible to find these places on your own.

Our driver dropped us off at a kosher café, where we enjoyed a leisurely lunch. With the warm weather, we sat outside in the sunshine and even enjoyed some ice cream for dessert—Mark had his pick from seven different vegan flavors.

After lunch, we walked to the nearest Metro station. Milan recently introduced a convenient system allowing passengers to enter and exit the Metro by simply tapping a credit card. The Metro was clean and quiet, making for an uneventful 20-minute ride back to our apartment in the city center.

A successful Wandering Jew day.

So much in one day!