MARCH 15-16, 2025: Palermo, once home to Sicily’s largest Jewish community, is the city with the most Jewish sites on the island. The Jewish presence in Palermo dates back to at least the 6th century, and during its peak in the medieval period, the Jewish population reached 5,000, making up about 15% of the city’s inhabitants. However, like in the rest of Sicily, Palermo’s Jewish community came to an end in 1492 with the expulsion of the Jews under the Alhambra Decree. Today, there are efforts to revitalize a Jewish community in Palermo.

Among the many Jewish artifacts we encountered in the city, I can categorize them into three groups: those in and around the former Jewish quarter, those housed in museums, and those various odd-and-ends that are peripherally related to Jewish heritage.

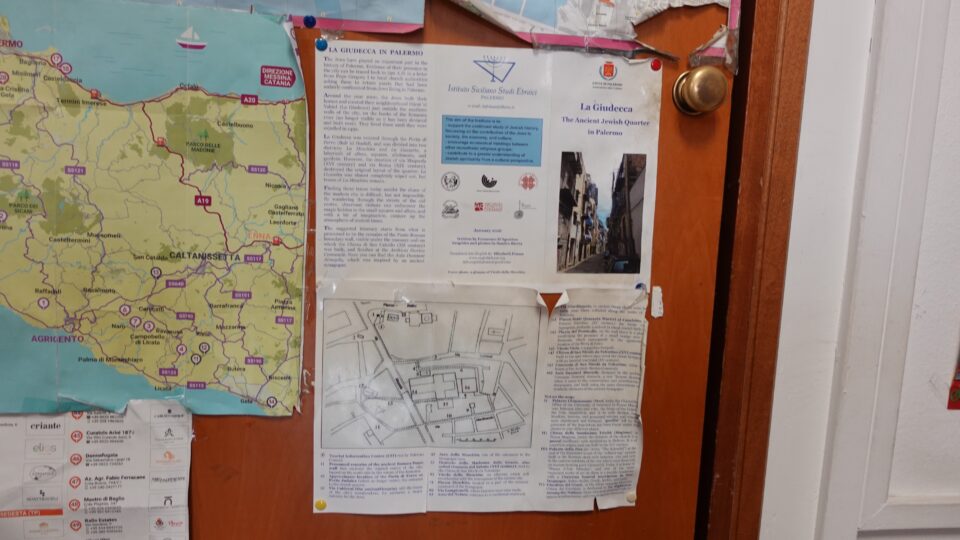

The former Jewish quarter lies just south of Piazza Bellini. On our way there, we came across an open Tourist Information office – a rare find in Sicily off-season. We asked if they had any resources about the Jewish history of the city. To our surprise, they did—a booklet listing numerous Jewish heritage sites. Unfortunately, they couldn’t find a copy for us to take, but they had one displayed on the wall, which we were able to photograph. This proved very valuable, adding a few more locations to our list and helping us pinpoint the sites we had already planned to visit.

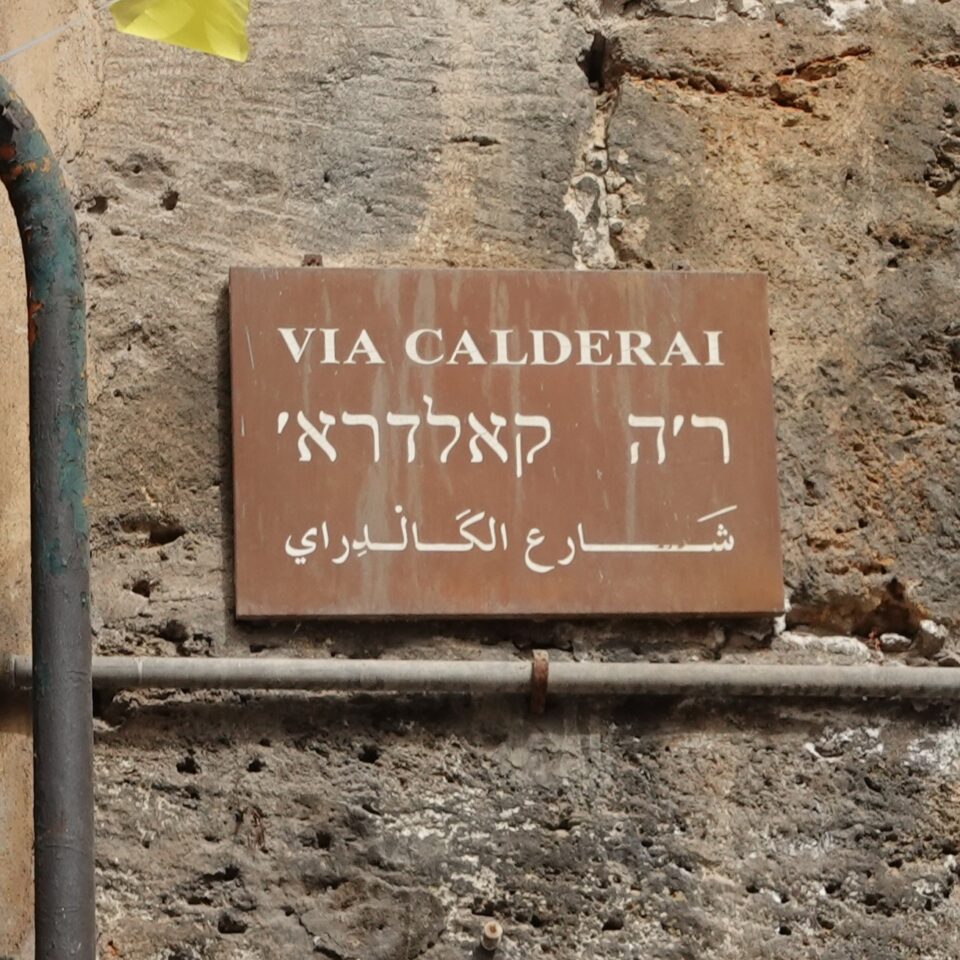

It is easy to know that you have reached the Jewish quarter because the street signs appear in three languages – Italian, Hebrew and Arabic.

According to the tourist information brochure, there are sixteen spots to visit in the area, some more relevant than others. The route begins right outside the tourist office, where the remnants of the medieval wall still stand. Nearby is the approximate location of Porto Judaica, which no longer exists. This gate was once the entrance to the Jewish Quarter.

Next, we walked down Via Calderai – one of the streets that belonged to the Jewish quarter. This street from the Middle Ages and until today is the home of many metalworks.

In medieval Palermo, the Jewish community was a vital part of the city’s economic and social life, engaged in a wide range of respected professions. Jewish physicians were especially esteemed, sometimes serving as court doctors. Merchants and traders played key roles in Palermo’s Mediterranean commerce, dealing in textiles, spices, metals, and dyes. Artisans, including goldsmiths, tailors, and metalworkers, were concentrated in the Jewish quarter, particularly along this street. Jews also worked as moneylenders at a time when Christians were barred from charging interest. Scholars and scribes contributed to intellectual life, producing religious and philosophical works, while rabbis and teachers maintained strong educational traditions. Some Jews were also involved in agriculture, working as tenants or leasing land from nobles.

At the beginning of Via Calderai is Arco della Meschita. “Meschita” is an old Italian word meaning “mosque” and in Palermo the Jewish area was known as “La Meschita”. Some say that this is because the synagogue was built where there originally was a mosque. Another idea is that the Jews and the Arabs lived side-by-side and the whole area was called La Meschita. An additional theory is that Meshchita in Arabic refers to place of worship, and can mean both a mosque or a synagogue. Hard to know which idea comes closest to the truth.

Immediately behind the arch is the entrance to the Ex Oratorio di Santa Maria del Sabato (former Oratory of Santa Maria del Sabato). But why “former”? This building, located within the historic Jewish quarter, was constructed in 1617 and has served various Christian congregations over the centuries. In 2017, over 500 years after the expulsion of Jews from Palermo, the Archdiocese of Palermo granted the oratory to the local Jewish community as a place of study and worship. The city of Palermo agreed to cover all restoration costs of this historic transformation—a church becoming a synagogue in an area that was once the heart of the city’s Jewish community.

Unfortunately, we saw no hint that this amazing transformation was taking place. One of the key women behind the initiative, Evelyne Aouat, has passed away, and a rabbi sent to Palermo by Shavei Israel, an organization that helps people reconnect with their Jewish roots, no longer lives on the island. Progress moves slowly in Italy, and hopefully this project will eventually happen.

The oratory is at the beginning of Vicolo del Meschita. In Italian, la via refers to a street or road, while la vicola is an alley. Vicolo del Meschita leads to Piazza del Meschita, what was once the outer courtyard of the main synagogue.

In Piazza del Meschita we came upon a large building whose architectural style subtly hints at being a synagogue. This is the rear side of the Municipal Historical Archive, designed by architect Giuseppe Damiano Almeyda in the late 19th century. It was constructed on the site of Palermo’s main synagogue and incorporated design elements from the former building.

From Vicolo del Meschita, the Jewish route passes Via Lampionelli, another street in the Jewish quarter, and turns down Via Giardinaccio. About halfway down the block is Arco del Notaro, an entrance to a traditional courtyard.

Then proceeding across Via Maqueda, the main street, you reach the Piazza Santi Quaranta Martiri al Casalotto, now mostly used for parking cars. In this square is the 15th century Palazzo Marchesi, where the entrance to a ritual Jewish purification bath – a mikveh, was found. The palazzo was closed and when we asked at the tourist office, no tours of the mikvah were available. The locked entrance doors lead to a courtyard where people now live, and Mark waited for someone to exit so that he could go in. He saw the courtyard of the palace, but could not locate where the mikvah entrance was.

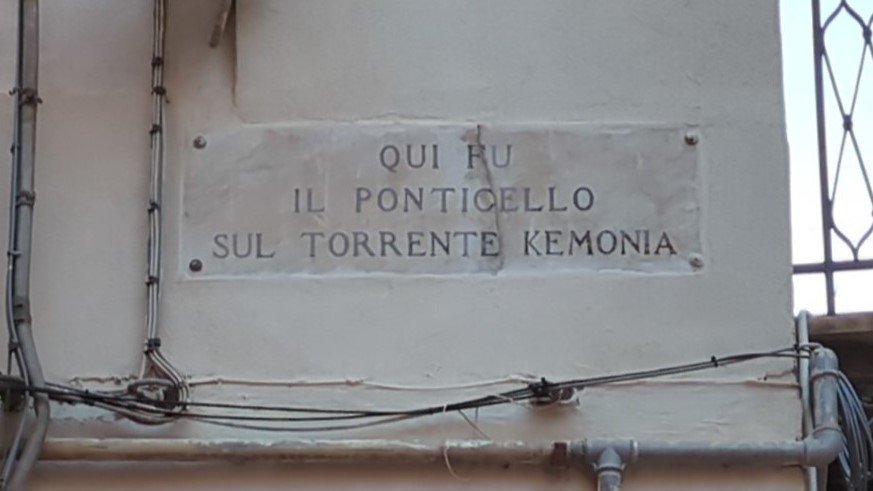

At the end of the plaza the Palazzo Marchesi sits in, is a plaque commemorating the location of a bridge over the river Kemonia, a river that was diverted due to urbanization and is no longer visible. It is the same river that once provided water for the mikvah.

At the other end of the bridge was the location of Porto Judaica – the Gate of the Jews, where we had started our route. We had come full circle, having traced the entire perimeter of La Meschita.

Returning to the main street, Via Maqueda, through Vicolo Viola (another small lane that was once part of the Jewish quarter), you reach the Chiesa di San Nicola da Tolentino (Church of San Nicola da Tolentino). A plaque inside the church marks the site as the former location of Palermo’s main synagogue. Shortly after their expulsion, on October 6, 1492, the building was sold by the Jewish community.

Next to the church, is the entrance to the archives. Interestingly, on the entrance gates, were posters for two Jewish-related exhibits that had recently ended.

Once you pass through the gates, you come to a courtyard with the main entrance to the archives, which was closed when we arrived. Now knowing what you can see inside, it was a mistake on our part not to make an effort to return when it was open.

The archive holds Jewish community records from before the 1492 expulsion and Inquisition trial documents against the Jews. ADD MARBLE SLAB. Also displayed here is a copy of the edict issued by the Spanish viceroy of June 18, 1492, which declared the banishment of all young and old, male and female Jews, on pain of death. This would have been remarkable to see.

Besides visiting the Jewish quarter, we visited five different museums in Palermo looking for remnants of the city’s Jewish past. Sometimes successfully, sometimes less so.

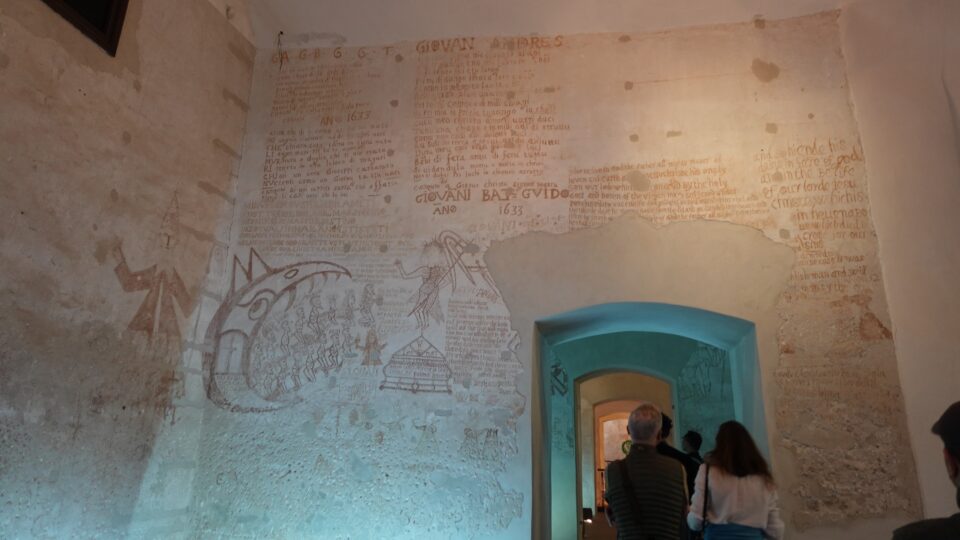

One museum that seemed to us obviously related to the city’s Jewish heritage is the Museum of the Inquisition, located in Palazzo Chiaramonte Steri – a building that was once the seat of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Palermo. From the early 17th century, countless individuals – including many converted Jews (conversos) suspected of secretly practicing Judaism – were interrogated, imprisoned, and tried here.

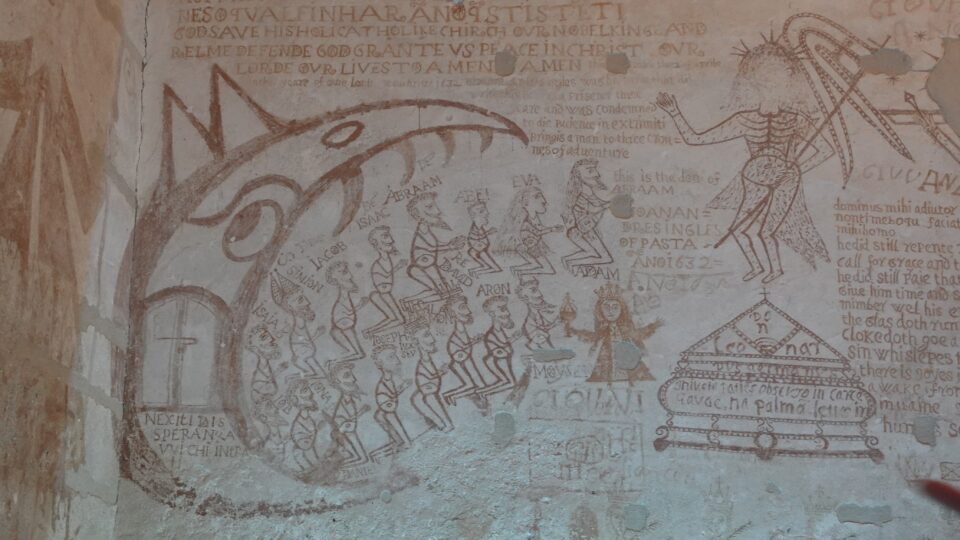

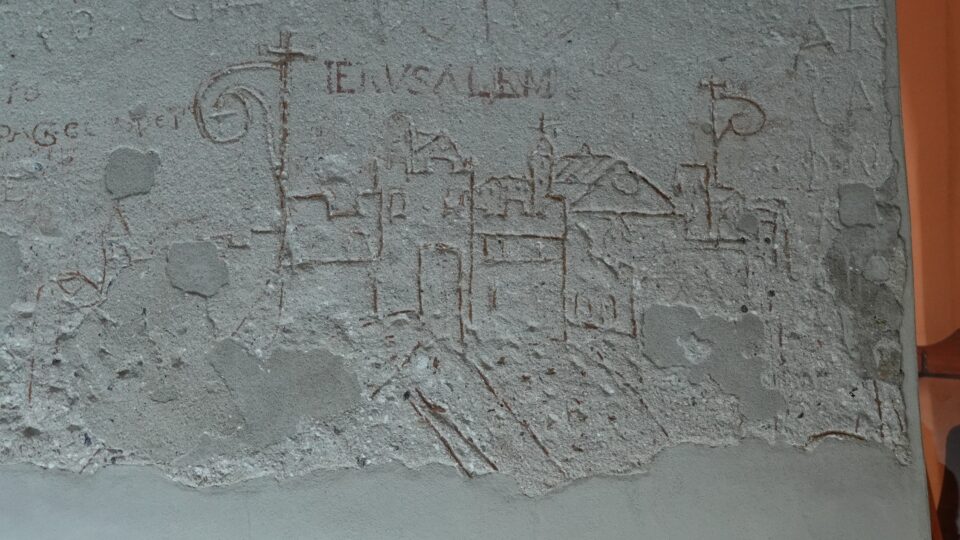

The museum can only be visited by guided tour, and during the one hour tour, to our surprise Jewish history was not really mentioned. The tour has three parts. The guide first takes you to see original prison cells where amazing graffiti etched by the prisoners was discovered. The graffiti was drawn using clay from the dirt floor mixed with spit and urine. The themes of the drawing were overwhelmingly Christian. The guide specifically mentioned that some of these cells were for clergymen that did not agree with the doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church. Where were the conversos held? More likely in windowless rooms in the basement. This part of the tour a also included a quick visit to a torture chamber.

Part two of the tour takes you to see The Great Hall, also known as the Sala Magna, a prominent feature of the Palazzo Chiaramonte-Steri. This hall is renowned for its intricately painted wooden ceiling, completed in the late 14th century. The ceiling spans approximately 28 by 8 meters and is adorned with a rich tapestry of imagery, including biblical scenes, mythological tales, chivalric romances, and allegorical figures, reflecting the diverse cultural influences of medieval Sicily.

When the Palazzo Chiaramonte-Steri became the seat of the Spanish Inquisition in Sicily from 1600 to 1782, the hall and adjacent rooms were repurposed for judicial proceedings and imprisonment.

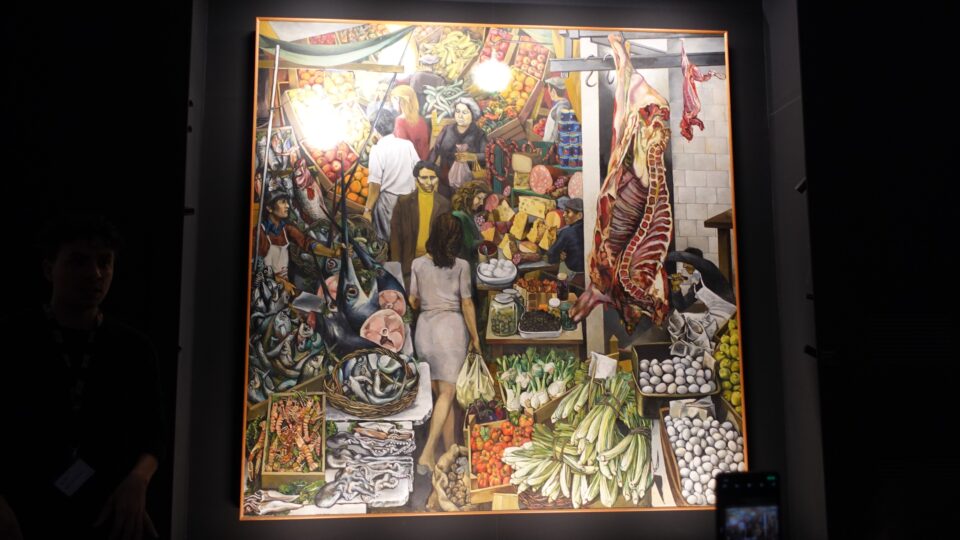

The last part of the guided tour is about a huge 1974 painting by Renato Guttuso, “La Vucciria”, which vividly portrays Palermo’s bustling open-air market of the same name. The painting has no relation to the Inquisition, except that it is housed in the same building where the seat of the Inquisition once was.

We know that the Museum of the Inquisition is relevant as a Jewish Heritage site, but the Jewish connection does not come across clearly in the guided tour. However, in contrast, in the museum gift shop, this is the only store on the island where we found a couple of books about Jewish Sicily. The two books were in Italian, none in English, one about the synagogue in Palermo and the other about La Meschita, the Jewish quarter.

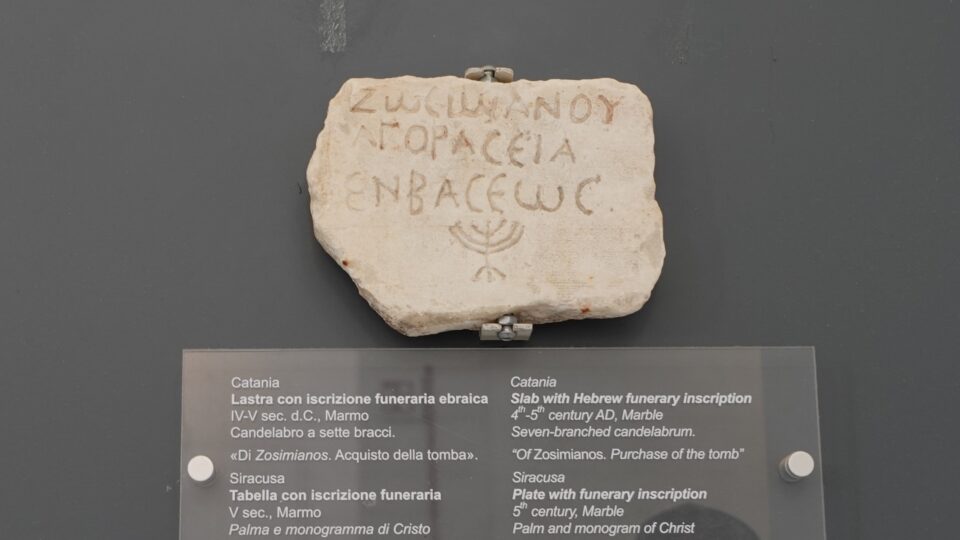

The Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum holds the tomb inscription in Greek of a Jew, oil lamps engraved with a menorah, and a medieval ceramic bowl bearing a Hebrew inscription. We easily found the tombstone fragment with menorah in a room near the entrance to the museum. After going through the rest of the museum, we did not find the items we were looking for or anything else from the medieval ages. We asked at the information desk and learned that all items from that time period are on display in the second floor, which is currently closed for renovations.

Another museum we visited was the Regional Gallery of Sicily, the largest art museum in Palermo. It is housed in Palazzo Abatellis, a 15th-century Gothic-Catalan palace that was converted into a Dominican convent.

According to our research, the museum houses a rabbi’s Hebrew funeral epigraph. We carefully walked through the entire museum and asked several staff members about it, but were unable to find it. Near the entrance, there was one room that was closed to the public, accessible only by a rickety “non-walkable” staircase, where we noticed what appeared to be tombstones — perhaps the epigraph is kept there.

In the center of the cloister at the Church of the Magione stands a historic well, relocated here in 1943 after surviving the wartime bombings that destroyed the monastery where it once stood. It is believed the well was originally constructed using repurposed Jewish gravestones. After the expulsion of the Jews from Sicily in 1492, many cemeteries were left abandoned, and over the centuries, their stones were gradually reused in buildings throughout the island.

Looking closely, at the top of the sides of the well, is a Hebrew inscription. The Hebrew letters are clearly visible, but too much of the text is missing to be able to understand what it says.

On the day we left Palermo, we drove to the Castello della Zisa, or Zisa Castle, a 12th-century palace that today houses the Museum of Islamic Art. The museum tell the story of how Muslim, Christian, and Jewish cultures interacted and influenced each other in medieval Sicily.

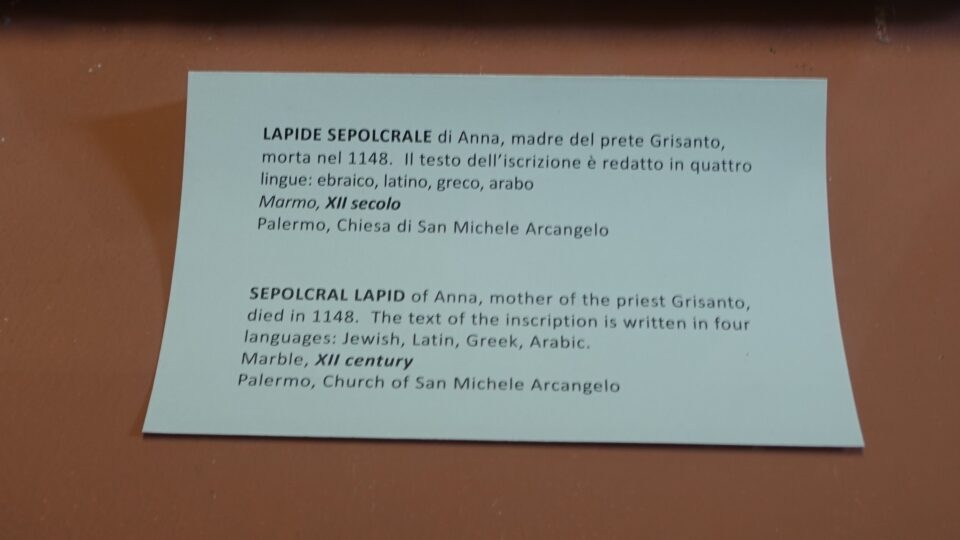

We went there to find a funerary stele (grave marker) of a woman with an inscription written in four languages: Hebrew, Arabic, Greek and Latin. It dates from the 12th century, during the Norman rule of Sicily, and reflects the extraordinary cultural and religious coexistence of that time.

In addition to the Jewish quarter and the museums, in Palermo we came across a few odds and ends that were more loosely connected to Jewish heritage.

During our visit there, Palermo was hosting an exhibition of photographer Enzo Sellerio, with his 1950s, black-and-white photos of the city displayed in the very spots where they were originally taken. We stumbled upon several of them as we wandered through the city. According to the biographical notes on the exhibition signage, Sellerio was born in 1924 to an Italian father and a Russian-Jewish mother. Although according to Jewish law he would be considered Jewish, we found no indication that he identified himself as such.

In the heart of Palermo’s historic district, is a small, tranquil public space dedicated as the Garden of the Righteous. It honors individuals who stood against oppression in various contexts, including those who saved Jews during the Holocaust.

The last site I want to mention related to Jewish Palermo is a plaque honoring Alexander Hoffman. In 1938, Italy’s Fascist regime under Mussolini enacted antisemitic Racial Laws that applied throughout the country, including Sicily. Although Sicily’s Jewish population was small—due to their expulsion in 1492—those who remained or had returned were fully subjected to these discriminatory measures. The laws stripped Jews of civil rights, normalized antisemitism, and paved the way for later persecution and deportation during World War II.

Alexander Hoffmann (1883–1976), who came to Palermo in 1914 for work, was deported to an internment camp following the enforcement of Italy’s 1938 racial laws. He was released in 1940. Today, a plaque near the entrance of the apartment building where he once lived reads: “Here lived Alessandro Hoffmann, victim of the brutal racial laws of 1938.” The plaque was unveiled during a Remembrance Day ceremony dedicated to preserving the memory of those who suffered antisemitic persecution.

In conclusion, on the one hand, Palermo had many Jewish sites for us to explore; on the other, it’s disquieting to realize that this handful of remnants is all that remains of a once-thriving community.

——————————————

To see the exact location of all places mentioned in this post, download the Wandering Jew app from your mobile phone App Store. To learn more about the app, see the Wandering Jew website.

0 comments on “Jewish Palermo”Add yours →