AUGUST 18, 2024: The day started with a 45-minute drive east from Besalú towards Castelló d’Empúries, another town in Catalonia with a Jewish past.

The drive there was mostly through flat agricultural land. There were many sunflower fields in different stages of growth – some dried out while others still green. As usual in Spain, distant mountains provided the backdrop.

Castelló d’Empúries, with a population of about 11,000, is larger than Besalú (population about 2500), but it is still a small town, not a city.

Google Maps took us to our first destination (“You have reached your destination on the right”) but between us and our destination was a large dry moat that had once surrounded the medieval city wall. In general, Google Maps has not been as reliable as we are used to. In the short time we have been here, it has steered us down pedestrian walkways, asked us to drive the wrong way on one-way streets, and to drive in alleyways clearly too narrow for a car. It is still our navigation app of choice, but we don’t follow it blindly anymore.

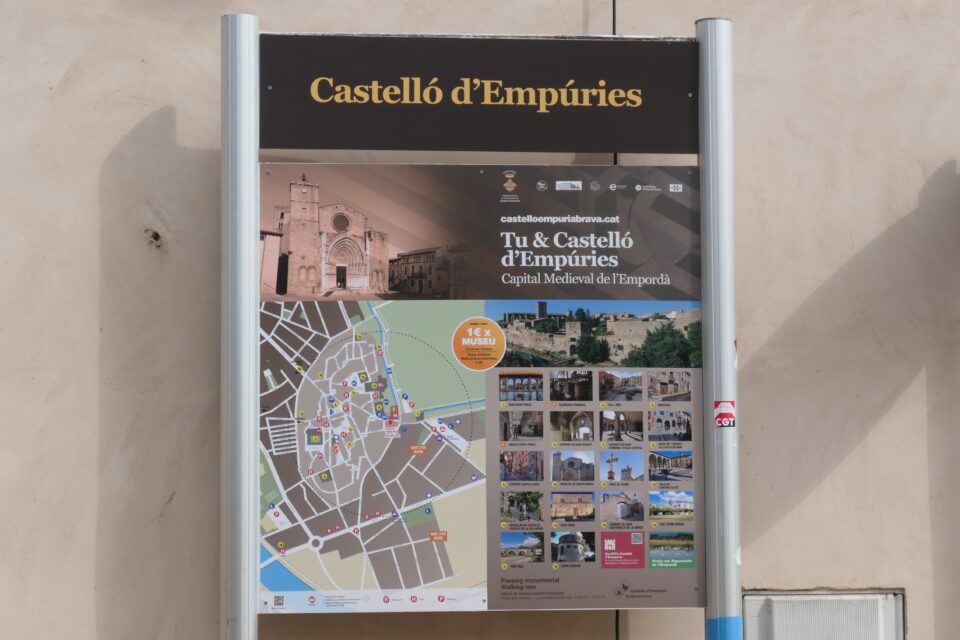

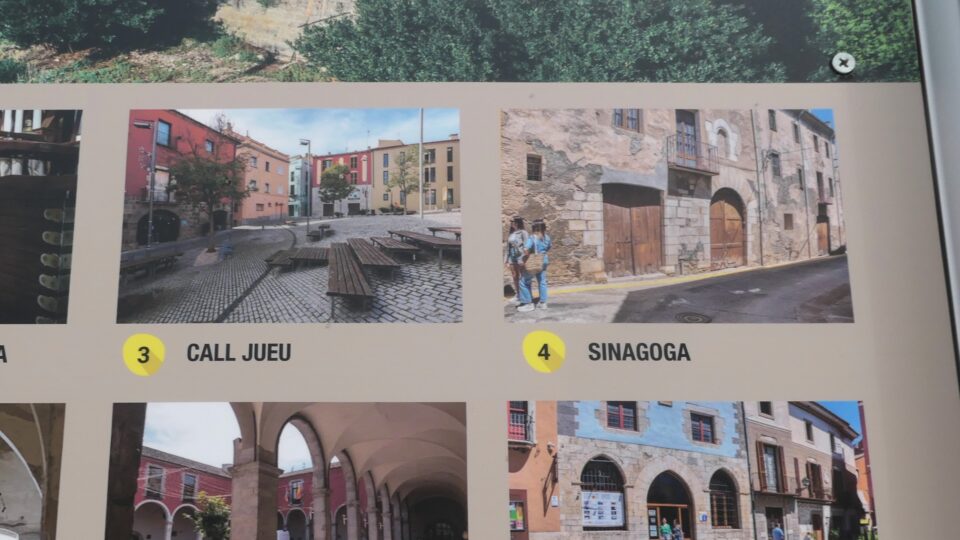

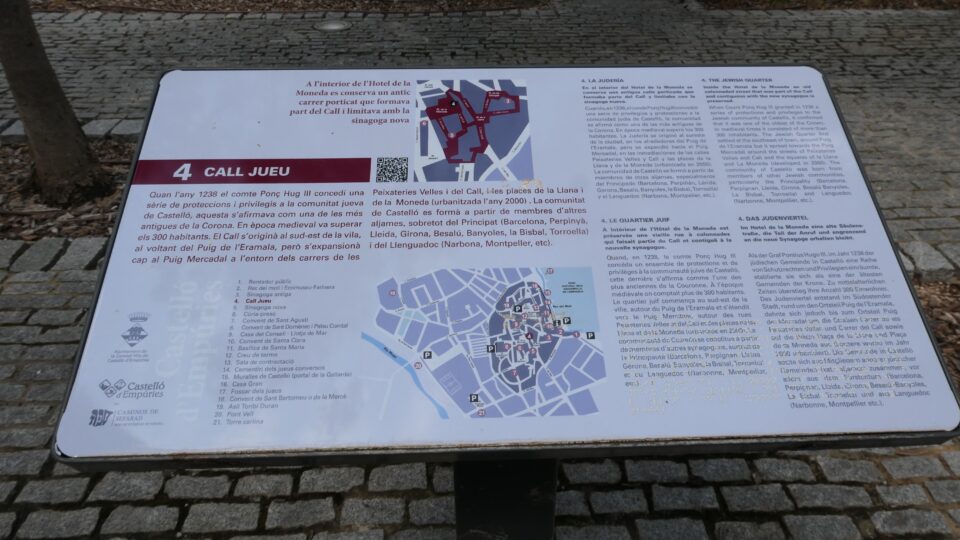

We found a nearby parking lot and walked into the town. Right at the entrance to the historic district was a map and a listing of the town’s attractions and we were happy to see that they included the Jewish Quarter (Call Jueu) and the Synagogue.

The history of the Jews of Castelló d’Empúries is similar to the Jews of Besalú. The community flourished during the Middle Ages when some 2,000 people lived in the town of whom about 300 were Jews. They were engaged in professions like moneylending, medicine, and trade, contributing significantly to the local economy. The Jewish quarter, or Call, was located within the town’s medieval walls.

However, like other Jewish communities in Spain, the Jews of Castelló d’Empúries faced increasing persecution during the 14th century, including the devastating pogroms of 1391. By 1492, following the Alhambra Decree, which expelled all Jews who refused to convert to Christianity, the Jewish presence in Castelló d’Empúries disappeared.

We entered the historic district of the town. It was made of low connected houses with small terraces mostly pastel colored – mustard, cranberry, olive and many shades of beige.

Our first destination was the Santa Maria Basilica. When you first enter this gothic cathedral, on your right are two large baptismal fonts both carved from the same stone – the large one used for christening adults, the small one for children. In February 1417, many of the Jews of the town were gathered in the square in front of the basilica and over 100 of them were taken into the church and baptized against their will using these same fonts. This was the first wave of mass conversions in the area. The fonts continue to be used to baptize infants till today.

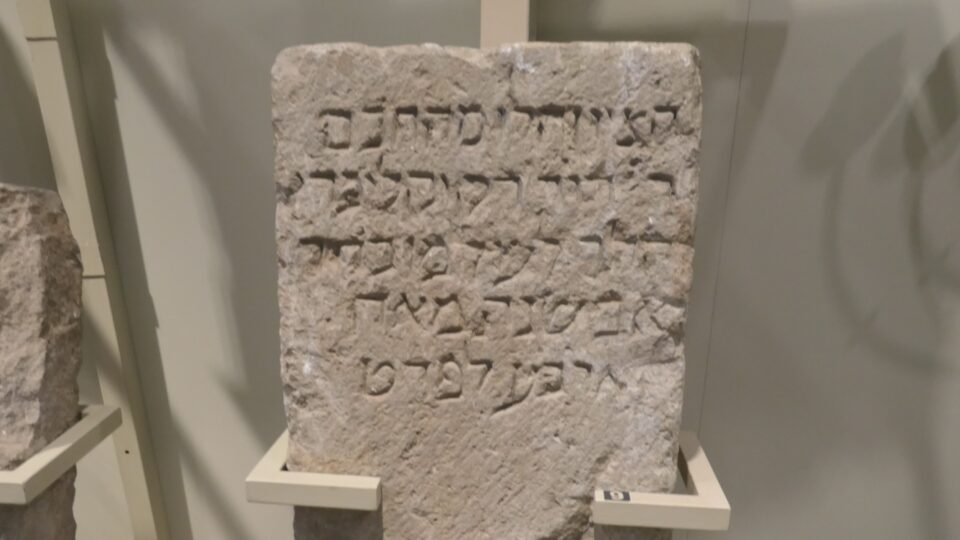

Also inside the basilica is a Parish Museum and in the small courtyard of the museum is a tombstone with Hebrew writing. This is a 15th century Jewish gravestone.

Once you exit Santa Maria Basilica and go around to the back of the building, you reach the Cemetery of Converted Jews. The Jews that had been baptized were buried in a separate section of the Christian cemetery. The area today is mostly a paved walkway, offering beautiful views of the surrounding countryside. Except for a sign about the cemetery, nothing of the cemetery remains.

While writing this blog and looking for a photo of this basilica, I noticed that one of the windows on the front façade is decorated with a Jewish star. This is something we missed while there, but here in the photo it is clearly visible – a Catholic church with a Magen David in the window. In Castelló d’Empúrie, the basilica was built during the years that the Jewish community lived here – perhaps this was the work of a Jewish craftsman?

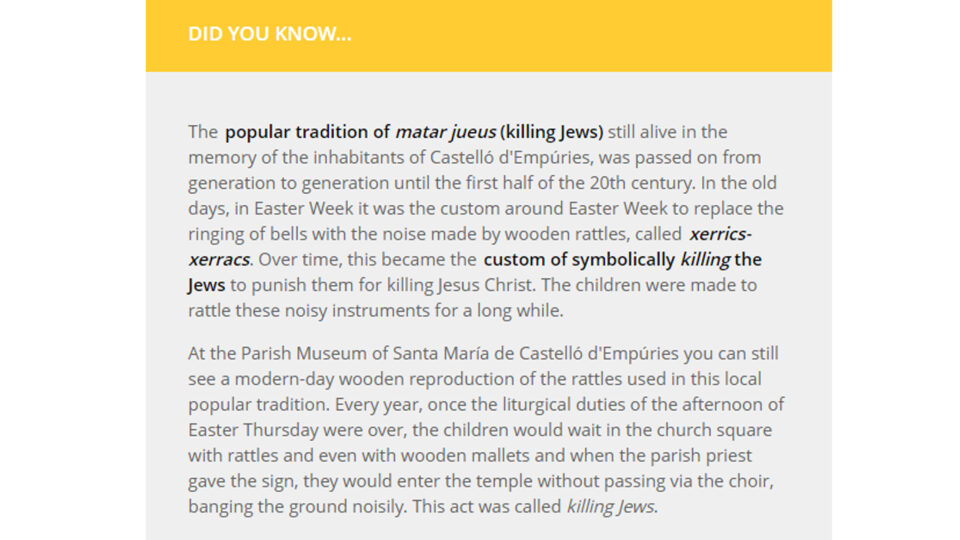

Another surprise (a mouth-open in amazement surprise) is when searching for information about the basilica, I discovered the following on the town’s visitor guide:

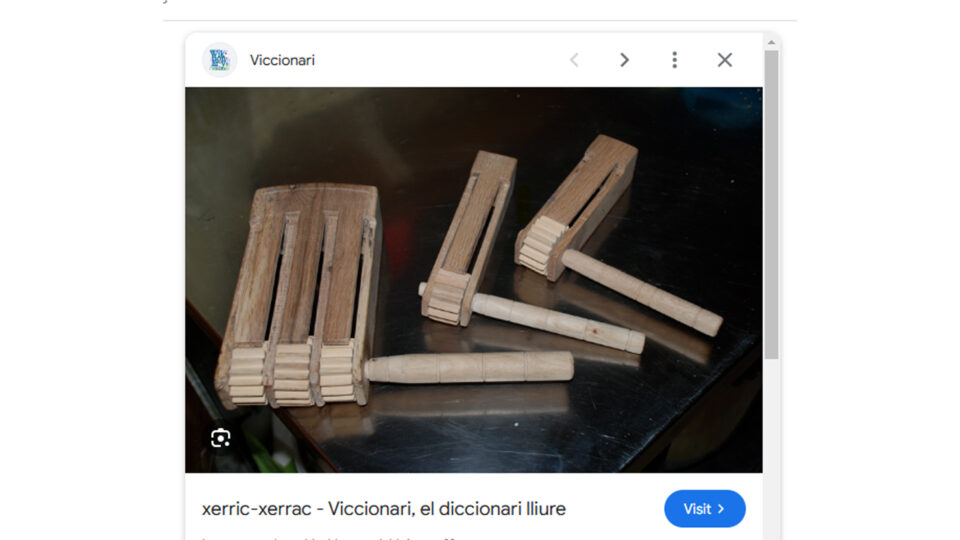

Basically, it says that the tradition of symbolically killing the Jews to punish them for killing Jesus continued until the 20th century! In Castelló d’Empúrie, during Easter Week, the children in the congregation made noise with wooden rattles called xerrics-xerracs and this act was called killing Jews. When I searched for images of xerrics-xerracs, I got photos of noisemakers identical to those we use on Purim! The custom of using a grogger to make noise when the name of Haman is read out during the reading of the Megillah has its origins in the 13th century, when Jews and Christians lived here side-by-side. Could the Jewish custom be the inspiration for this local Christian tradition?

More likely, both these traditions might have come from a Catholic practice that pre-dates both of these customs. In the three days from Thursday before Easter until Easter Sunday (called the Paschal Triduum), it was prohibited to ring the altar bells. On these three days, they would use wooden noisemakers called crotalus instead. In the Wiki article about crotalus, it even mentions that the groggers that Sephardic Jews brought with them to the New World after the 1492 expulsion, were used as crotalus. Interesting how the religious practices intertwine.

One last item to mention about the basilica, is that on its northern side, there is what is called the Sculpted Head of a Jew. This is something we also did not notice while we were there, but now in my photos I can somewhat see its location. The Jew, the only sculpture on that side of the building, is facing the Jewish quarter of the town. The Jewish quarter was our next destination.

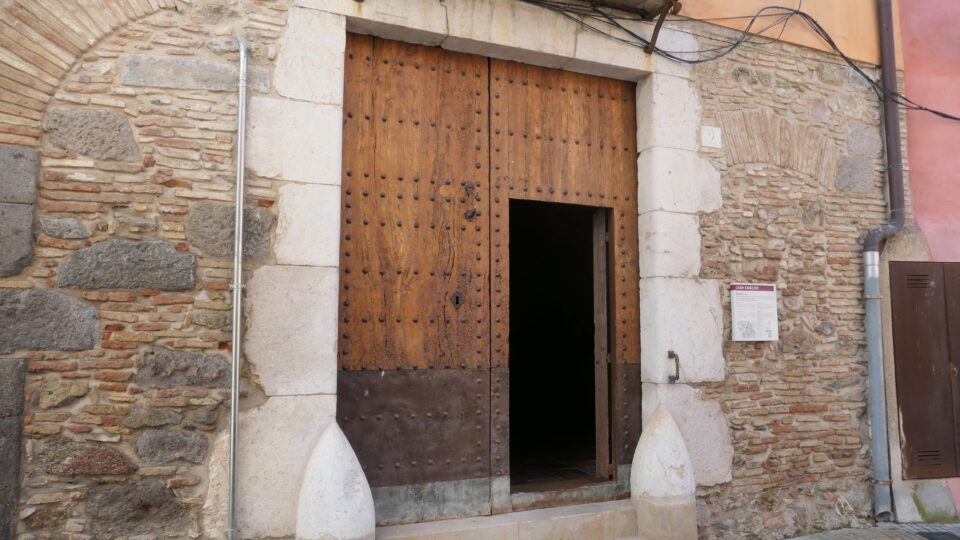

We first passed the location of the Old Synagogue. This synagogue, in the older Jewish neighborhood in Castelló d’Empúrie, was in use until the New Synagogue was built in the late13th century. After all the Jews were forced to live only in the Call in 1442, it was then reopened and used until the expulsion in 1492. Today, a building known as Casa Sanllehi occupies the site.

The streets next to the Old Synagogue are the location of the small, first Jewish Quarter in Castelló d’Empúrie, the Old Call. It is situated in the heart of the historic district and is made up of a few narrow, winding streets.

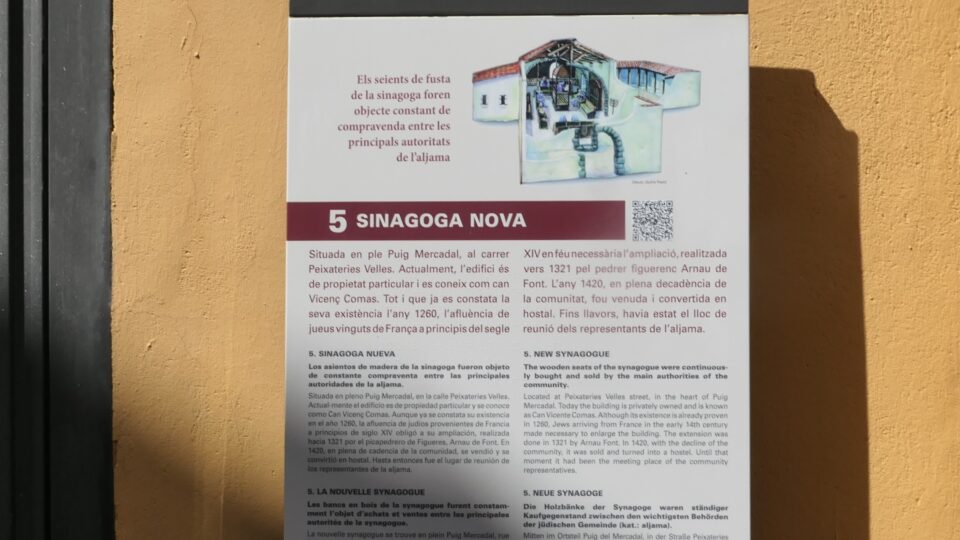

As the Jewish population grew in the 13th century, their neighborhood expanded into the New Call, closer to the count’s palace. In the New Call was the New Synagogue. Today the building that was once this synagogue, is a private home. Between 2014 and 2015, several archaeological excavation were carried out inside the building, revealing the oldest remains of the synagogue and a possible mikveh.

Our next stop, just down the block, was the Cúria-Presó Medieval History Museum. The museum building was constructed around 1336 and served as both a court and a prison. On the ground floor of the museum is a small room dedicated to the Jewish past of Castelló d’Empúries.

Like in most of the museums that we visited on this trip that display Jewish artifacts, the collection usually has two themes – one about the local Jewish history, and another about general Jewish rituals. This museum was no exception.

In the Jewish room was a collections of Hebrew headstones from the medieval Jewish cemetery of Castelló d’Empúries. Town residents were encouraged to donate these tombstones to the museum instead of keeping them in their homes. Most of them are the actual tombstones and one is a replica of the tombstone we had already seen in the basilica courtyard.

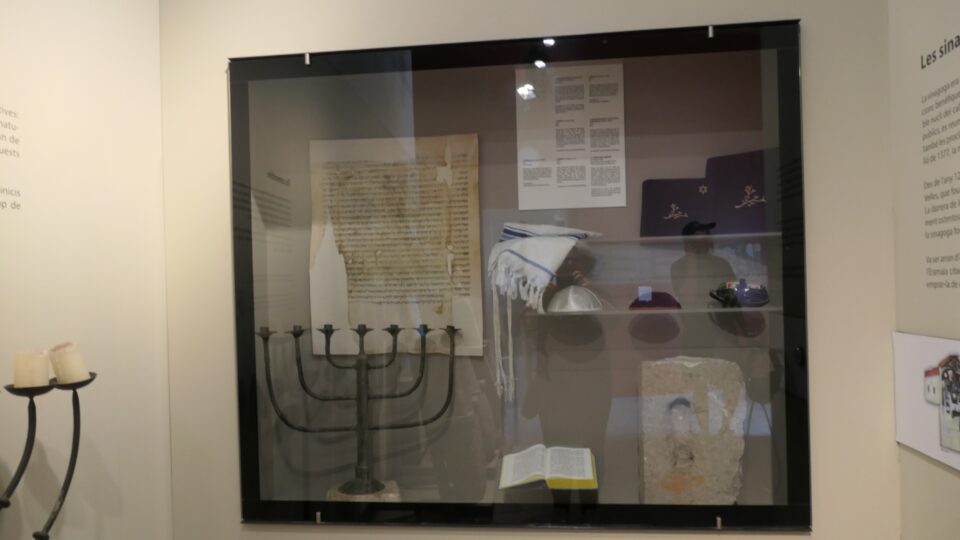

To show Jewish rituals, they had an exhibit case with a tallit, a ketuaba (a wedding contract from May 3rd 1377 between two Jewish residents of the town), kippot, a prayer shawl and a Hebrew prayerbook. Unfortunately, the Hebrew prayerbook was displayed upside down. We let the person at the front desk know and he said he would pass the information to the exhibit curator. I wonder if it is now fixed.

Near the museum is a small empty square, marked as the former location of the Jewish quarter. The building with the arched doorway today is the Hotel de la Moneda. Inside the hotel are the remains of a medieval street with colonnades that leads to the new synagogue Unfortunately we found the Hotel closed, and could not see exactly what was there.

After returning to our car, we drove a short distance to see the site of the Jewish cemetery. It is a small area of grass outside the town walls, along the inclined banks of the river. Besides the sign, saying this was the location of the Jewish cemetery, there is nothing to see.

The town of Castelló d’Empúries is located about 9 km inland. We then continued our drive, over the mountains towards the coast.

Our next destination was Portbou – a coastal resort town all the way in the northeast corner of Spain near the border with France. Its proximity to the border, made it a key destination for refugees fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II.

The drive to Portbou was spectacular. On one side the sea and on the other side the mountains that hug the coast. The vegetation felt like home – many of the same plants as in Israel: Tamarisk trees (Eshel Abraham), Oleander, Bougainvillea, Sabra cacti, olive trees, etc. Resort towns dotted the coastline with many white houses on the hills overlooking the water. Here, people walked the streets in bathing attire.

After about a 45-minute drive, we reached Portbou, a small coastal resort town with a spectacular cathedral nestled between the mountains and the sea. We came here to see the memorial for Walter Benjamin.

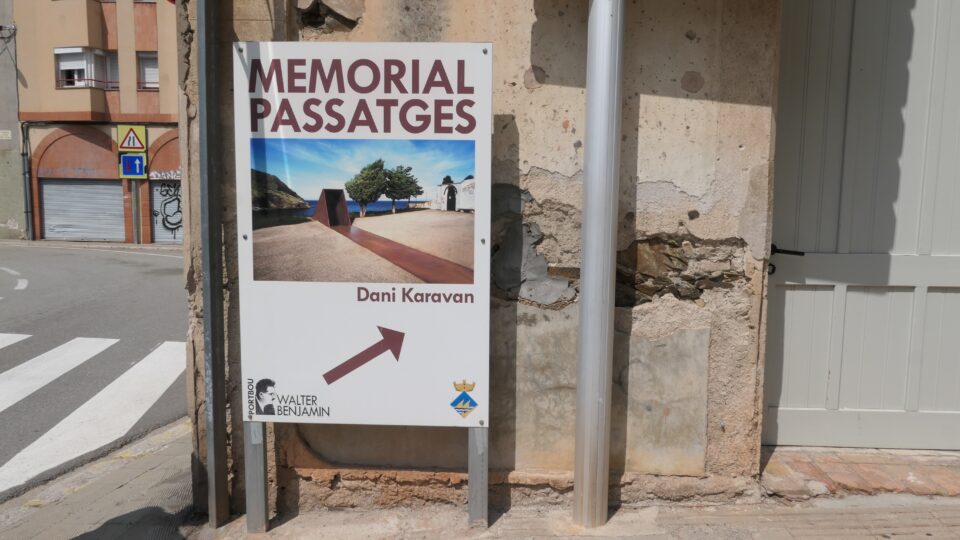

The Walter Benjamin Memorial, known as “Passages”, is a tribute to the brilliant German Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin, who committed suicide in Portbou in 1940 when he was denied entry into Spain and threatened with deportation back to Germany. Designed by Israeli artist Dani Karavan, the memorial was completed in 1994 and is located near the cemetery where Benjamin is buried.

The memorial sits at the top of the hill above the town, overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. You can enter the monument and go down a steep set of stairs to a glass floor landing hovering over the water far below. A place of contemplation.

I was surprised at the amount of publicity the memorial received all around this town. Signage for it appeared everywhere. It was even pictured on the Welcome to Portbou sign at the entrance to the city.

Once we had paid our respects at the memorial, we returned to our car for the long drive back to Besalú.

Tomorrow begins our family reunion – all 20 of us together in an old, converted farmhouse high in the mountains northwest of Besalú. Can’t wait.