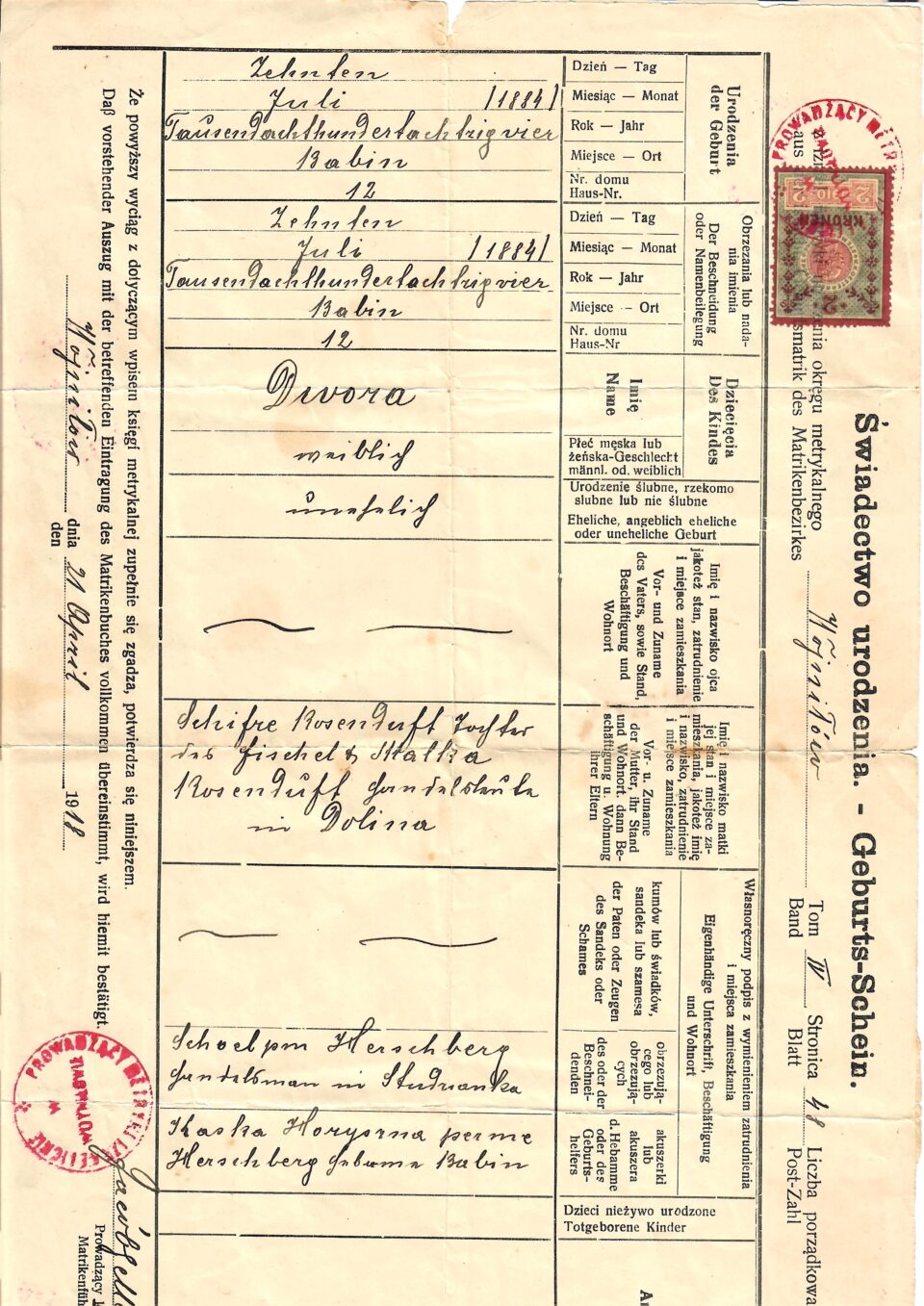

Oma, whose real name was Dvora (Dora) Feuerstein, née Bergwerk, was born on July 15, 1884, in Kalusz to Marcus Mordechai Bergwerk and his wife, Shifra. At the time, Kalusz (now Kalush, Ukraine) was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, specifically the region of Galicia— a major center of Jewish life at the time.

Recently, while going through the boxes of documents found in my late mother’s apartment, I came across her birth certificate – with her first name and correct date of birth, but no last name. Once translated, it was a bit shocking to see that it clearly stated she was born “illegitimate.” However, after speaking with a friend knowledgeable about Jewish history from that time and region, I learned that this was not uncommon. Civil marriage licenses were often expensive, so many Jewish couples would marry in a religious ceremony before a rabbi without obtaining a civil license. When they later went to the hospital to give birth, the absence of a civil marriage record meant their children were officially documented as illegitimate. Within this context, the certificate made much more sense.

Oma and Opa had five children, though only three survived to adulthood. Their firstborn was my grandmother, Frieda, born in 1909. She was followed by Ese in 1910 and Hilde in 1913. After Hilde, Tony was born in 1915 but tragically died at around four years of age, in 1919. Their youngest, Bubbie, was born in 1917 and lived to about five years of age before passing away in 1923.

All the children were born in Herne and the three that survived to adulthood all managed to reach Palestine by 1937. More of their stories later.

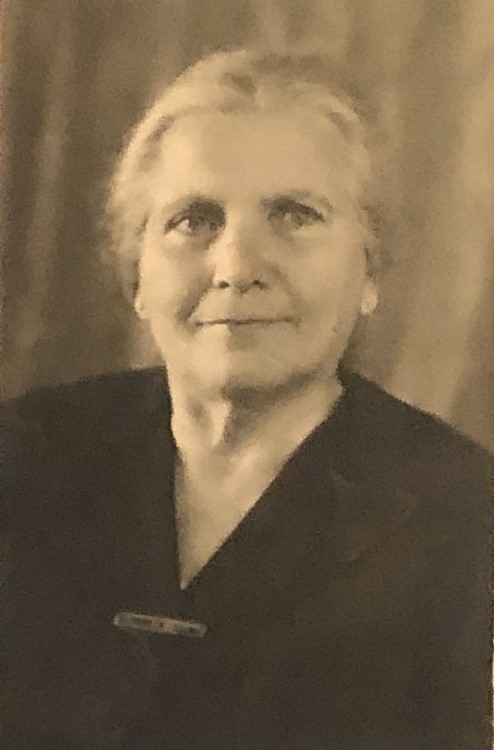

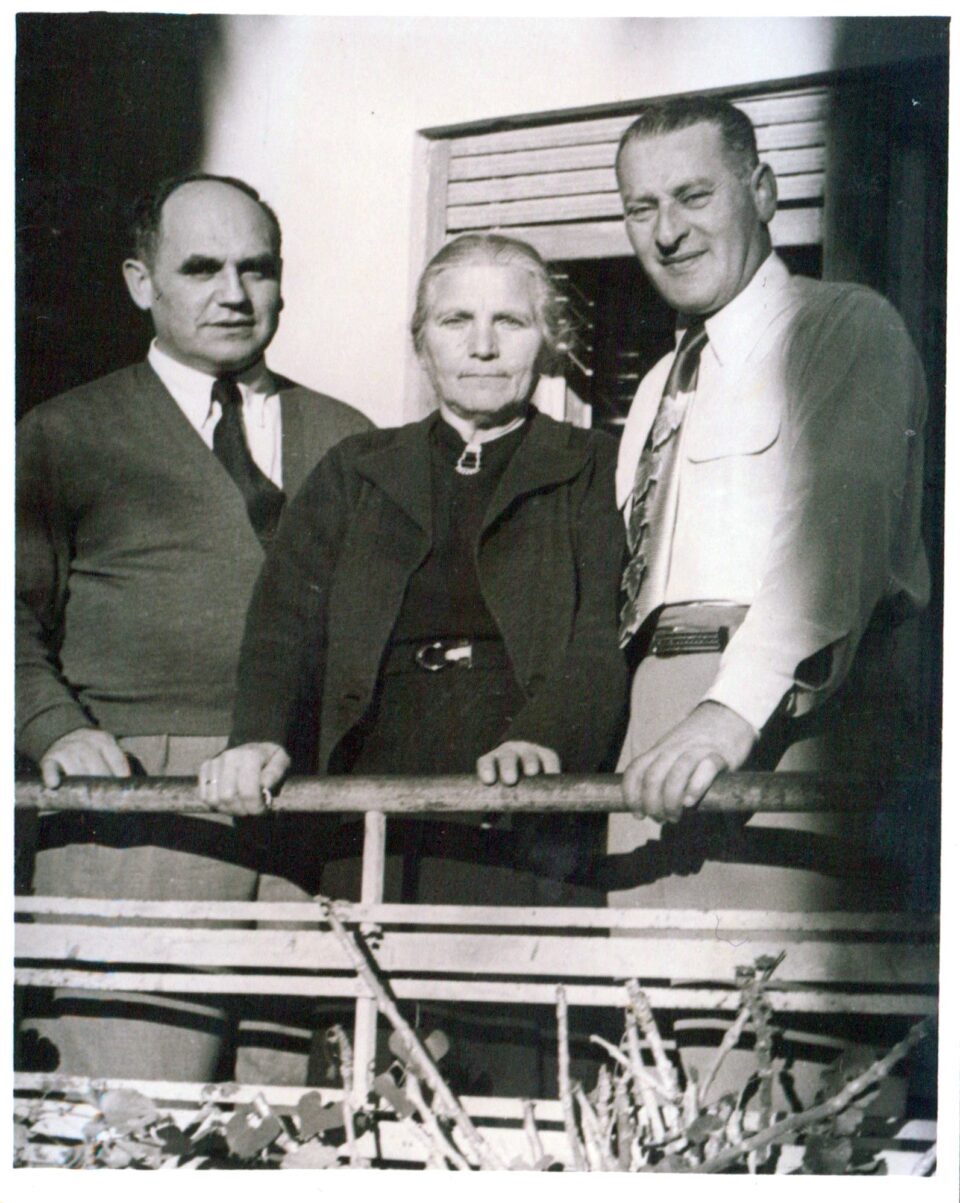

Oma passed away in 1974, and I was 16 at the time – old enough to remember her vividly. From the age of four, we lived in the USA, but every other summer, we would come to visit the family in Israel. During those visits, spending time with Oma was always on the agenda. I remember her as a small, frail woman, standing dignified and straight, usually wearing a simple cotton frock and always strikingly beautiful with her blue eyes and white hair.

One memory that stands out clearly, is when we were visiting Israel in 1968, the company Stock 84 invited all those born in 1884 for a day trip. She returned from the trip with a blue and white kova tembel printed with the Stock 84 logo. I might still have that hat somewhere…

When I asked my uncle Uri (my mother’s brother) what memories of Oma and Opa he would want the younger generations to know, he didn’t hesitate: “How much they were part of our daily lives.” He recalled how his mother, Sabti, would send him and his younger brother Dani, each with an egg in hand, to Oma’s house. Eggs were rationed at the time, and Sabti didn’t want Oma to use her own rations on the children. Oma would prepare the eggs for the boys, and Uri admitted that Oma’s cooking always tasted better than Sabti’s.

He also shared a story about Oma from Germany, before she moved to Palestine. Once Sabi and Sabti got married, they moved to Cologne. At that point, Sabi was still a medical student—he and Sabti married in 1928, but he didn’t complete his exams until 1930—and they were poor, money was very tight. Every week, Oma would send food parcels from Herne to Cologne to help them. For me this story was especially meaningful. Over the years, my own mother often went out of her way to support me, and I’ve always tried to do the same for my children. It felt good to realize that generous help to our offspring is a family trait—one that’s been passed down through generations.

For more photos and documents about Oma, go to here