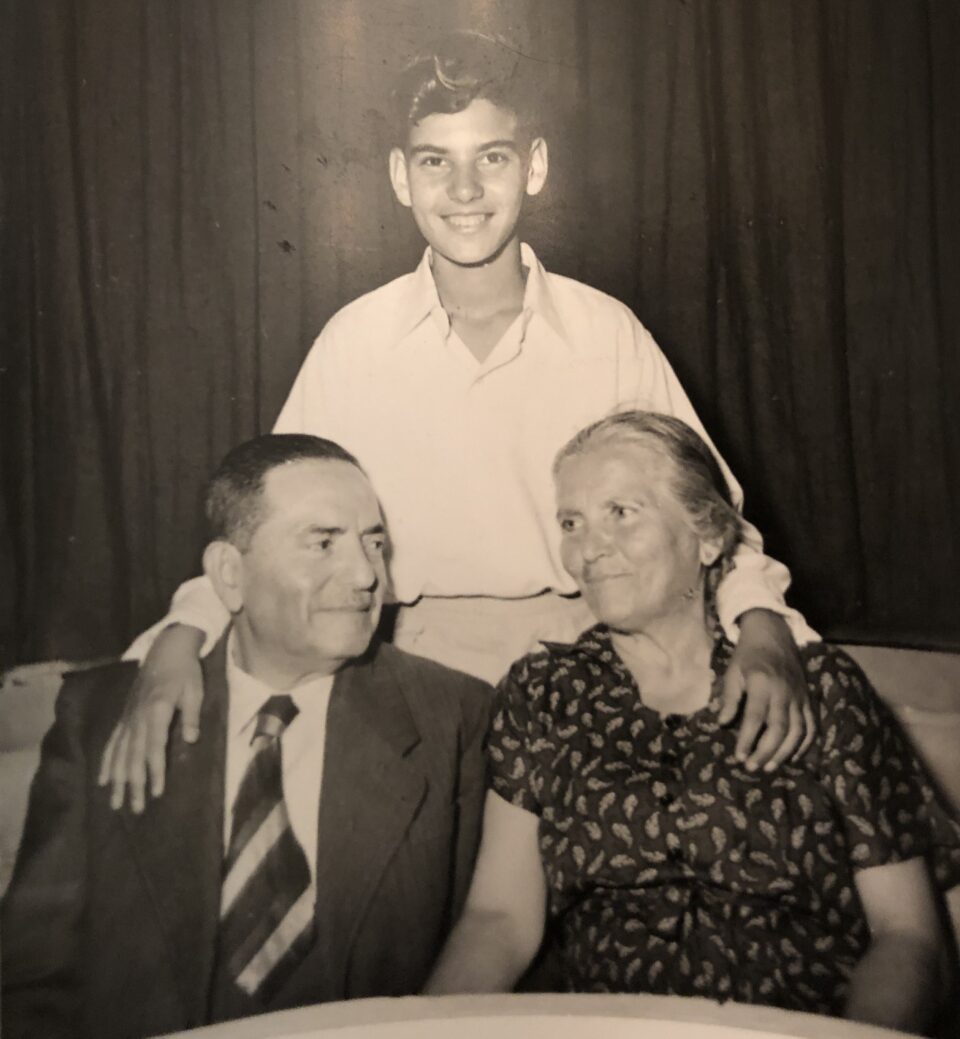

Of my eight great-grandparents, I met only two of them – Dora and Moshe Feuerstein, whom we affectionately called Oma and Opa, the parents of my mother’s mother.

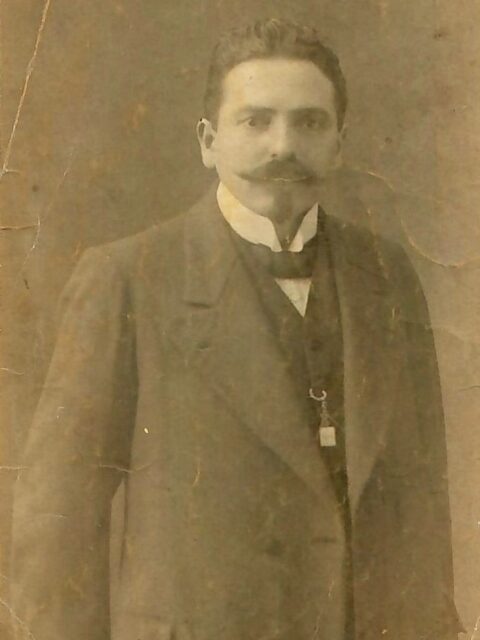

Opa, whose real name was Moshe Feuerstein, was born in 1878 in Perehinske (now in Ukraine), which at the time was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the region known as Galicia, one of the major centers of Jewish life in Eastern Europe for centuries. He lived to the age of 90, passing away in 1967 when I was 9 years old. I remember him mostly from photographs.

Oma, Dora Feuerstein, on the other hand, is vividly etched in my memory – a beautiful woman, even in her advanced years.

When I knew Oma and Opa, they lived in a small ground-floor apartment in Petah Tikva, a place that always smelled like a blend of delicious home-cooked food and the musty scent of timeworn belongings. Their tiny kitchen had a simple Formica table, where Oma would sit and play Solitaire for hours. Her face would light up with a huge smile whenever I walked in to visit her.

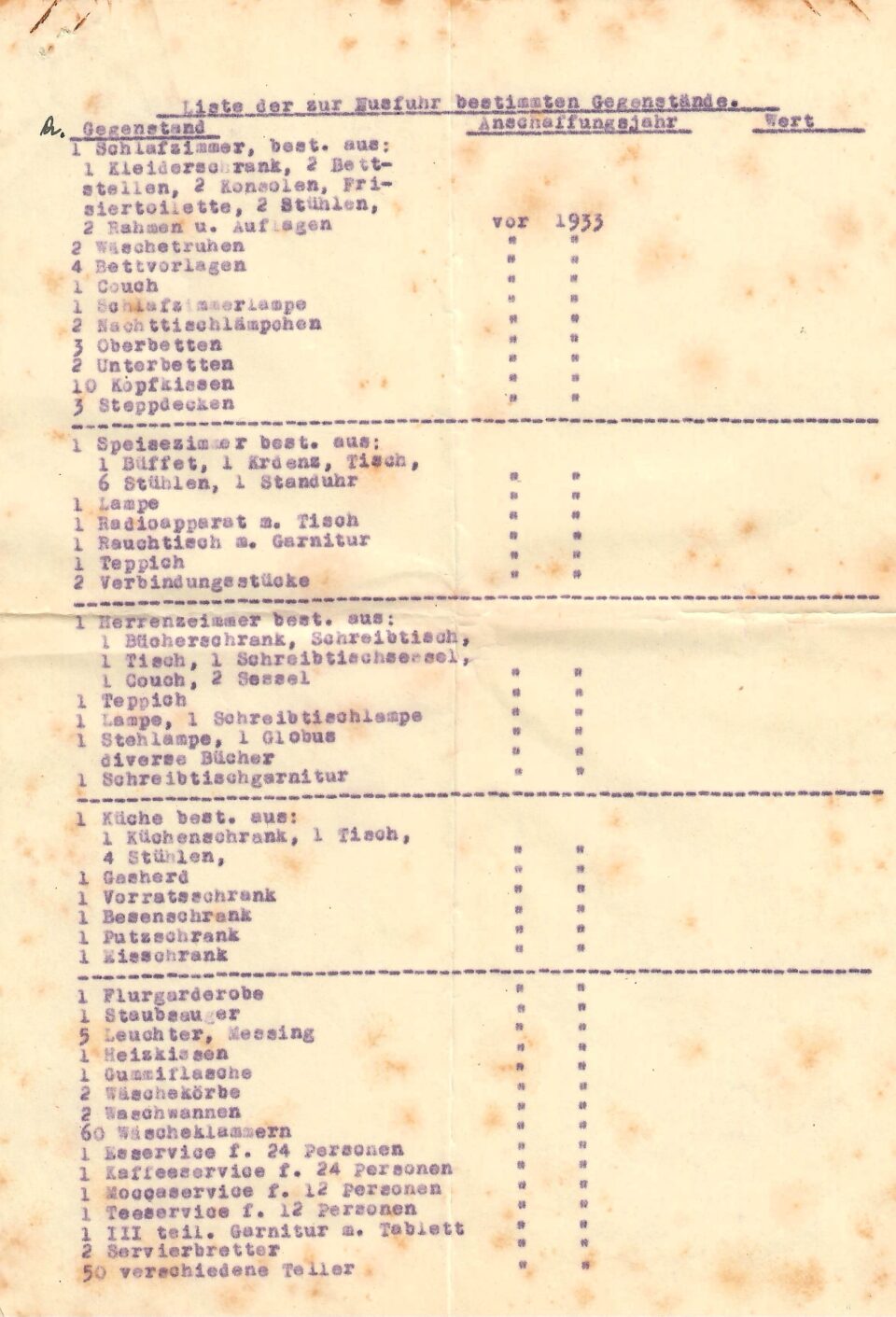

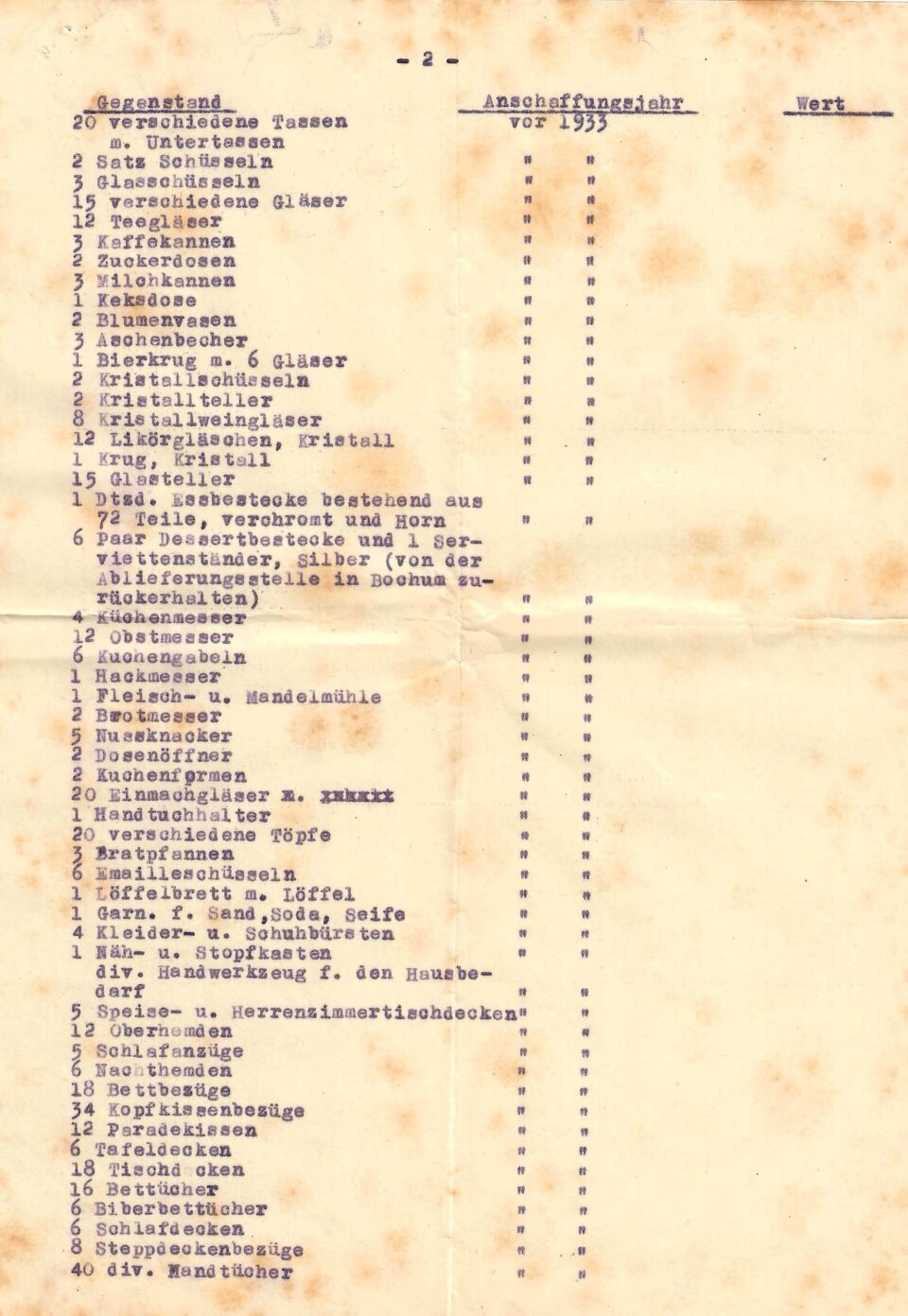

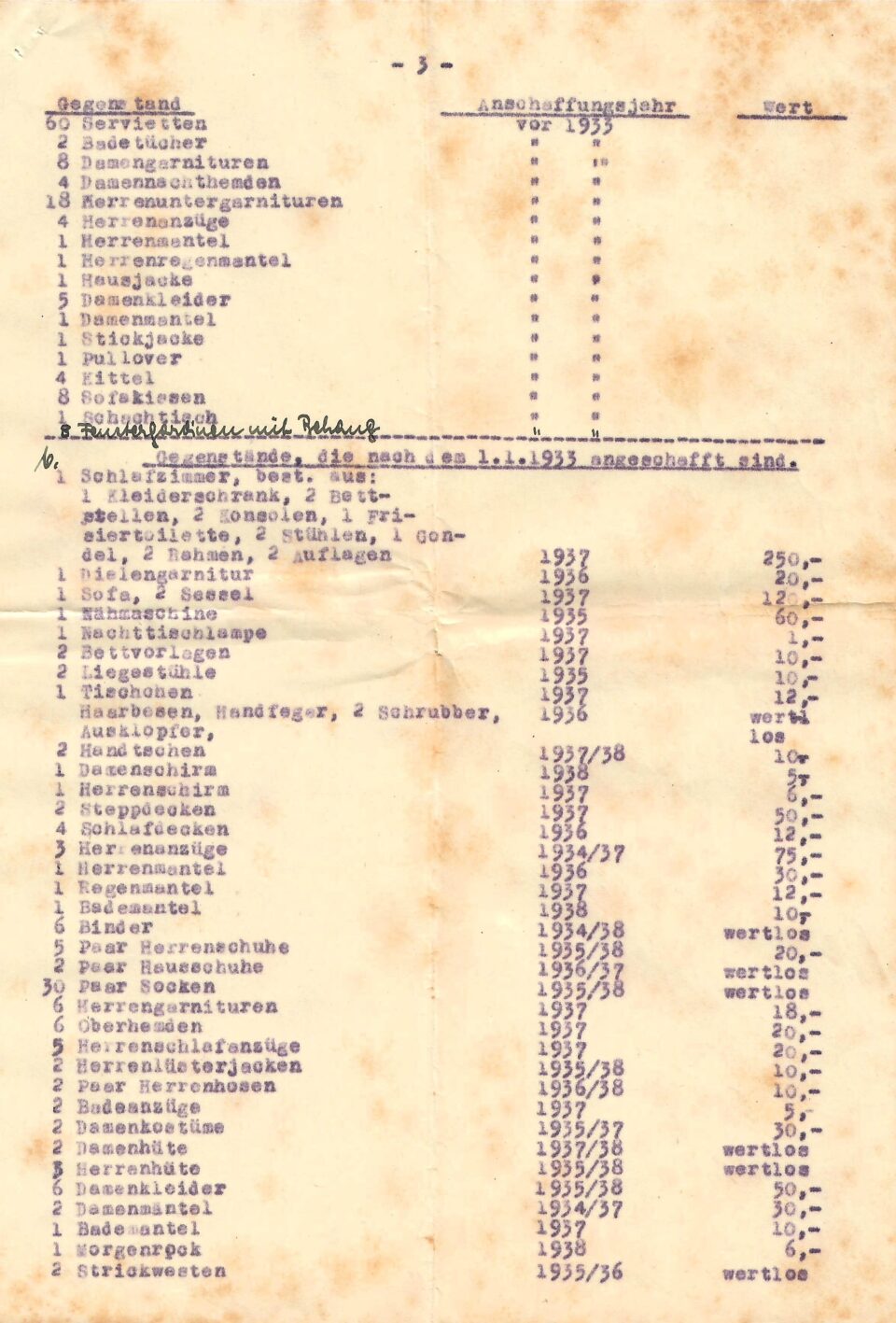

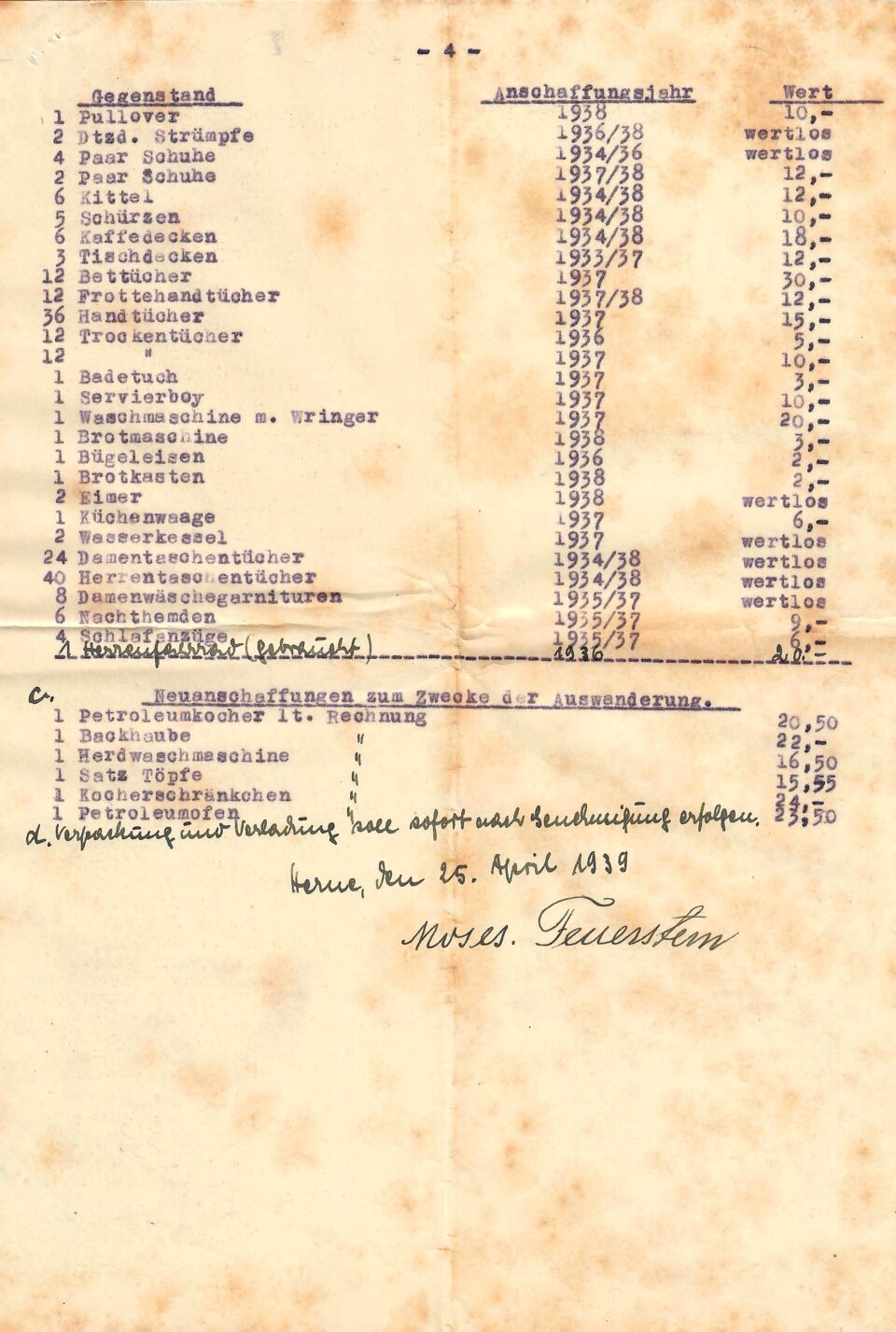

Their furniture, brought with them from their furniture store in Herne, Germany, was far too big for their small apartment. Today, those antique pieces are scattered among their descendants. I have their dining room table and chairs, though it’s not quite as they had it—Sabti, my grandmother, reupholstered the chairs with vinyl. It may not be as elegant, but for a household with many children, it was certainly more practical.

I remember when I received the table when we moved to Israel, my thought was that it was old-fashioned, not keeping with the style I wanted my house to have. However, the connection of the table to our family history has kept it with me all these years, so that even tonight, we will be sitting around it for our Passover seder.

Before emigrating to Israel, Oma and Opa lived in Herne, Germany in a large apartment above their furniture store.

The stories most closely associated with Opa are what happened to him around Kristallnacht—the violent pogrom carried out by the Nazis on November 9–10, 1938, when Jewish synagogues, businesses, and homes across Germany and Austria were destroyed, and thousands of Jews were arrested or killed.

In Herne, as a store owner, Opa was deeply respected by both his staff and customers, many of whom were not Jewish. So much so, that during Kristallnacht, local townspeople stood guard around his shop to protect it from destruction.

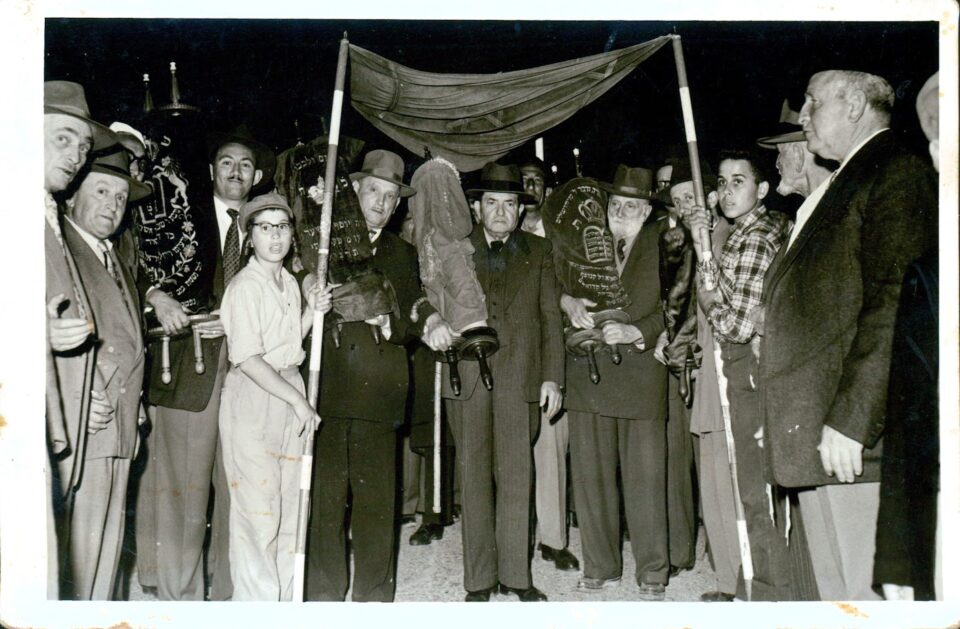

That night, however, the Nazis succeeded in setting the Herne synagogue on fire. In the morning, while the roof was still burning, Opa ran inside and rescued the Torah scroll along with a silver yad (a pointer used for following the text when reading the scroll), taking both for safekeeping.

Later that same day, the Nazis came and arrested him, sending him to a labor camp. There, the prisoners weren’t given meaningful work—instead, their clothes were stuffed with heavy rocks and stones, and they were forced to march up and down a hill all day. The conditions were brutal, and few survived.

Opa held out until December 26, celebrated as Second Christmas Day in Germany. On this day, the commander of the camp, perhaps drunk, was feeling generous, and he released anyone who had a birthday that same day. Luckily, Opa turned 60 that day and was allowed to go back home to Herne, on the condition that he leave Germany.

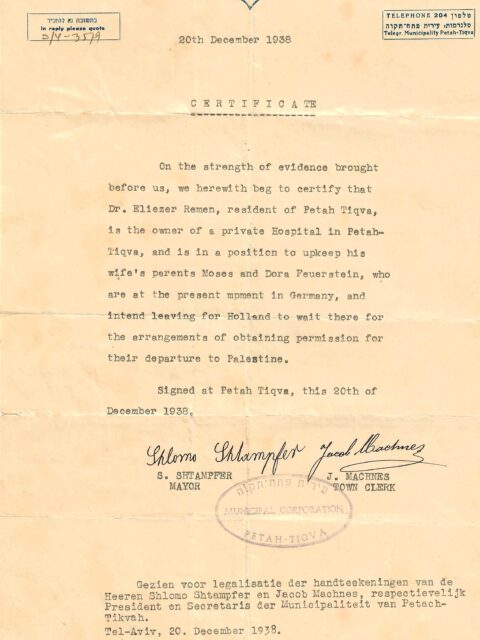

When he returned to his family in Herne, Oma, his wife did not recognize him – the six weeks in the camp had changed him so much. Once back home, Oma and Opa prepared to leave the country as soon as possible to Israel (Palestine at the time). The family members already in Palestine prepared the required paperwork for them to immigrate.

While packing their belongings for the trip, German soldiers watched over them. It was Oma’s job to distract the soldiers, so that Opa could quietly pack and hide their valuables.

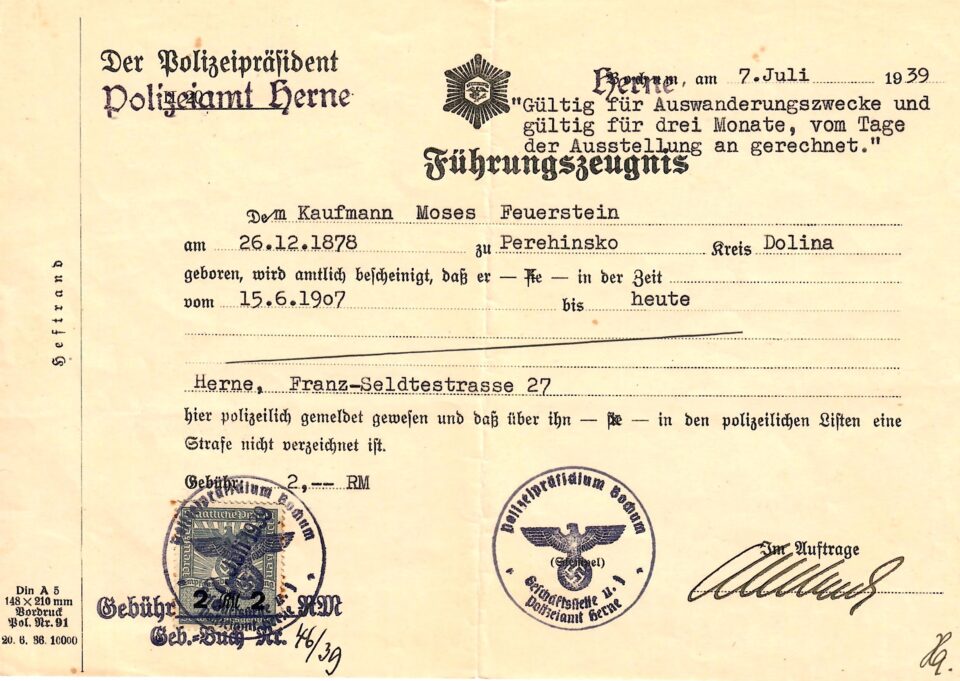

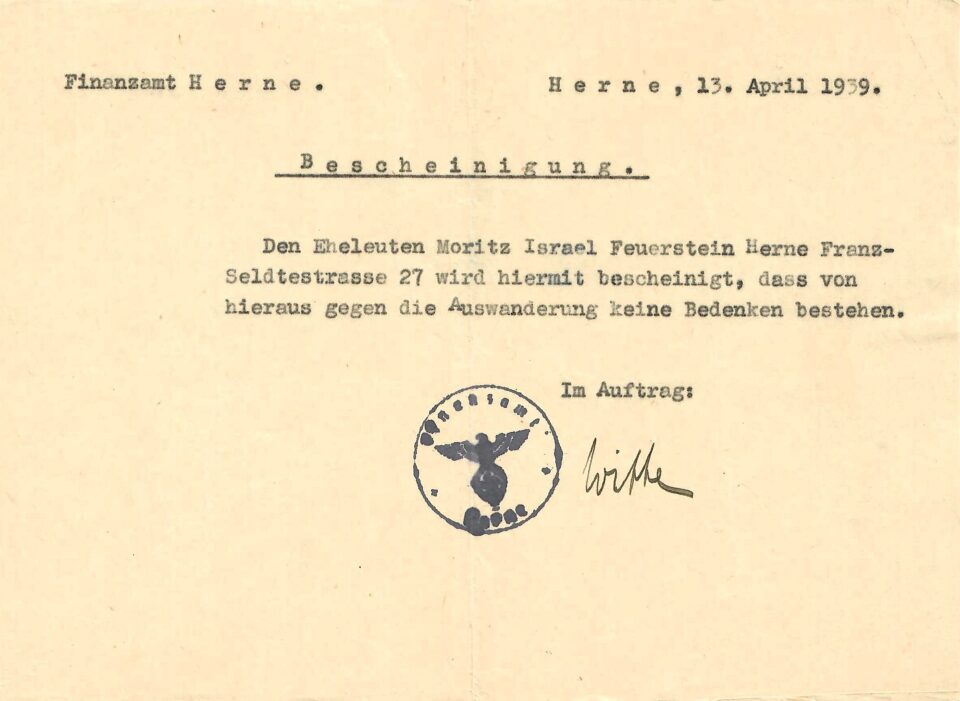

After leaving Germany in July 1939—on one of the last boats to legally immigrate to Palestine—they arrived in Petah Tikva, not far from where their daughter, my grandmother had settled a few years earlier. Their apartment was located at 34 Keren Kayemet Street.

When I was born, Opa was already 79 years old. I remember him as a quiet, kind, old man, who walked slowly with a cane. He passed away in 1967, at the age of 90, and is buried in the Segula cemetery in Petah Tikva (Section ח, Row סט, Stone 8).

In general, we know very little about his life – from Perehinske where he was born to Herne, Germany is over 1500 km (930 miles) How, when and why did he go to Herne? How did he meet my great-grandmother? What was the name of the labor camp he was in? All unknown.

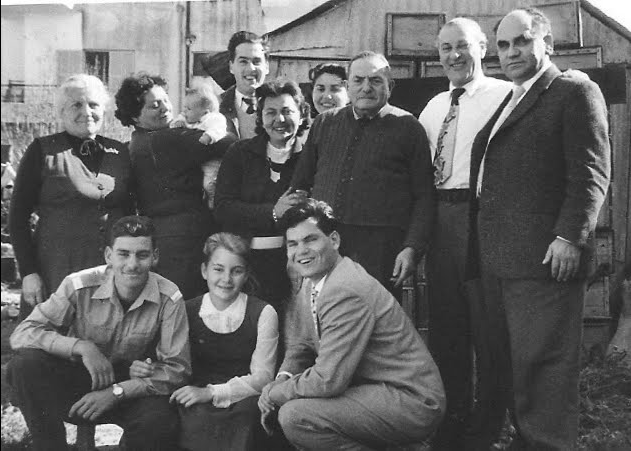

We do know his mother’s name was Adele and we know his father was David HaLevi Feuerstein, and that Opa was one of several children. From looking at records on the internet and deciphering what is written on the back of old family photographs, it seems that he had at least two brothers – Yaakov and Yosef and a sister named Berta.

What is confusing is that Opa’s sister Berta married someone also called Yaakov Feuerstein – I presume a cousin with the same name as her brother. Berta and Yaakov had two boys, Isbert and Helmut, who would be Opa’s nephews. The family lived in Recklinghausen, about 12 km north of Herne. All four were murdered in the Holocaust, when Isbert was about 15 years old and Helmut 11.

Opa’s brother Yosef also was born in Perehinsko, in1892, 14 years younger than Opa. He was a merchant and married to Lote neé Bitkover. Prior to WWII he also lived in Recklinghausen, Germany. Yosef and his family also were murdered in the Shoah.

His other brother Yaakov was married to Mirale and they had at four children that survived the war – Leo, Adele, Leah (also known as Klara) and Alex. Leo and Leah lived in Haifa and Adele on Kibbutz Ein Hantziv.? Alex, who became an orthodox rabbi, lived in London.

Leo Feuerstein, a nephew of my great-grandfather, who lived in Haifa made a family tree. If I remember correctly, he traced the Feuerstein family all the way back to the Ramban. What happened to Leo, and to the tree, I do not know.

What happened to the Torah scroll that Opa rescued on Kristallnacht? When Oma and Opa moved to Palestine several months later, they took the Torah and yad with them. Once in their new home, Opa donated the Torah to a local synagogue.

After Opa’s passing, his son Ese went to a rabbinical court, arguing that the Torah had only been loaned—not permanently given—to the synagogue. The court agreed and returned the Torah to Ese, who kept it in his apartment. After Ese’s death, my husband Mark had the Torah examined and it was found to contain numerous small errors, making it unkosher. Hilde, Opa’s daughter and Ese’s sister, then donated the scroll to Bet Daniel, a Conservative synagogue in Israel, which accepted Torahs that didn’t meet strict orthodox standards.

Hilde’s son, Ami Daniel, who now lives in the United States, heard the story of the Torah and retrieved it from Bet Daniel and took it to America, where he then donated it to [insert name of final synagogue or institution]. The silver yad that was once used to read the Herne Torah scroll is now in my sister’s home.

One other fact that we know about Opa is that he served with distinction in the Austrian army during WWI. His belonged to the communication corps and would climb poles to string phone wires. Once, while working, a bomb fell close by and he suffered a permanent hearing loss from the impact. Opa received two medals for his service – one an Austria – War Commemorative Medal (on the left below) and the other is a coveted Iron Merit Cross given for important services rendered in support of the war effort. Perhaps he thought this distinction would protect him during the Second World War. Unfortunately, we will never know.

I am now in the process of getting two stolpersteine, one placed in honor of Opa and another one for Oma, in front of what was once their home atop their furniture store in Herne, German. Stolpersteine are memorial stones that have the name of the person who once lived there and what happened to him. The dedication ceremony for Opa and Oma’s stolperstein is expected to take place in the summer of 2026.

One of the deliberations is what name to place on the stone. Opa was born Moritz, and in many of the documents we have about him, his name is Moses, and I knew him as Moshe. At the end, I decided that the name on the stone should be the same name he used on the invitation to Sabti’s wedding, which occurred during the time he lived in Herne. On the invitation he used the name Moritz.

More photos:

For more photos and documents about Opa, go to here